Clinical Infrapopliteal Disease

Critical limb ischaemia (CLI) typically presents as rest pain, tissue ulceration or frank tissue loss with gangrene, often accompanied by infection. Occasionally a patient may also present with claudication that is so severe that the patient is restricted to a few feet of ambulation. These patients sometimes have early rest pain on further questioning. Diabetics with neuropathy often skip the anticipated phase of claudication with progressive peripheral vascular disease and present with tissue loss as the first clear manifestation that the limb is threatened. The natural history based on conservative care is poor, with a short-term mortality rate of 10 %. Other risks include myocardial infarction and stroke (2 %), amputation (12 %) and persistent CLI (18 %).1 It is well known that the amount of blood flow required to heal damaged tissue is substantially more than that required to maintain intact tissue. For patients with digital ulcerations, perfusion restoration with straight-line tibial flow to the foot is typically required for at least 12 weeks and revascularisation directly into the angiosome appears to be associated with improved limb salvage rates.2

In the US and worldwide, healthcare delivery systems are faced with an ageing population and diabetes in near-epidemic proportions. Symptomatic infrapopliteal peripheral vascular disease is thus poised to be a major challenge to these healthcare systems. Lower peri-procedural risks, a more aggressive stance towards limb salvage and a greater understanding of the strategy and technique of percutaneous endovascular procedures make this approach a logical choice for near-term advances in its contribution to the management of CLI due to below-the-knee (BTK) disease. These techniques must not only be successful in restoring adequate perfusion levels but must also be economically viable, so that they are applicable across all societies.

It is also becoming increasingly apparent that the integration of multiple specialities will be necessary for successful clinical outcomes in these incredibly complex patients. In addition to the timely restoration of perfusion, treatment of CLI requires local wound care, pressure offloading, infection control, medical optimisation of co-morbid conditions, meticulous wound debridement and local toe or partial foot amputation, as needed, to save a functional limb. Prior to undertaking any definitive therapy, proper evaluation and documentation of the status of any infection, including osteomyelitis, must be undertaken. The anatomical obstructions that are present in patients with CLI are usually multi-level or, in the case of tibial vessels, multi-segment. Healing variables that require evaluation include the number of vascular levels that are obstructed, the patency of the plantar arch, the amount of tissue destruction that has occurred, the need for debridement or skin grafting, what potential conduit (such as a vein) is available should a bypass be required, the severity of co-morbidities and, finally, the nutritional status of the patient, as tissue healing requires significant caloric intake. The techniques for increasing perfusion to the threatened limb can be completed either with open surgical or percutaneous endovascular means in appropriately selected populations.

Surgical Infrapopliteal Treatment

Surgical bypass to the infrainguinal and infrapopliteal segments has a well-established history with documented outcomes. Five-year patencies for the saphenous vein may be approximated to 66 %, with even higher limb salvage rates in patients with CLI. The use of in situ vein bypass has led to the advancement of bypass grafting to more distal tibial vessels. However, if an adequate venous conduit is not present, prosthetic graft patency is less than 50 %.3 More complex bypass procedures have been created, such as a short-segment venous cuff, collar or patch, combined with prosthetic bypass material, or arm vein or composite vein bypass to the ankle or pedal arteries, which have shown some early success, but at a cost of substantial morbidity.4–7

Current Endovascular Treatment

Because of the significant co-morbidities that are present in this patient population, the use of endovascular techniques for revascularisation has increased. Endovascular procedures have not demonstrated the long-term patency of open surgical procedures but the clinical outcomes, as measured by limb salvage, appear to be similar and the percutaneous procedures are often easily repeatable, if necessary. The recently published Bypass versus angioplasty in severe ischaemia of the leg (BASIL) trial,8 which randomised patients with severe limb ischaemia to surgery or angioplasty, showed a cost benefit for angioplasty at one year, with similar clinical outcomes. With the improvement in low-profile percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) balloon technology, even diffuse tibial occlusive disease can be effectively dilated. Recent results of a large series (n=993) of tibial angioplasty have shown five-year limb salvage rates of 88 %, which certainly challenge those of surgical bypass. The re-intervention rate was only 13 %.9 Although plain balloon angioplasty is the cornerstone of endovascular care, there are other niche techniques that may be used for successful outcomes. Cutting balloon angioplasty has been evaluated in a registry format and has shown promise in complex disease such as bifurcation lesions.10 This registry of 73 limbs showed an almost 90 % limb salvage rate at one year with a 30-day mortality rate of only 1.5 %. Subintimal angioplasty11 and directional atherectomy are other techniques that have been studied in small series with short follow-up.12 The application of coronary stents is feasible and early haemodynamic results and limb salvage rates have been excellent in a recent series.13 In a multicentre study, patients deemed to be poor surgical candidates underwent excimer laser treatment for CLI. The six-month survival with limb salvage rate was 93 %.14 Even though each of these technologies has its benefits and drawbacks, there are no comparison data available between the different technologies to show an advantage over plain balloon angioplasty.

Long occlusions have often been difficult to traverse with a guide wire. However, even as surgical techniques have advanced for distal pedal or crural anastomosis, endovascular techniques have started to take advantage of any patent pedal vessels for successful retrograde wire access, adding another avenue for success.15,16 The utilisation of coronary drug-eluting stents in the infrapopliteal vasculature has demonstrated improved patency in focal tibial disease, but thrombosis has been observed and their use in the more common diffuse-lesion subset has not yet been studied.17–20

Drug-coated Balloons

Mechanism of Action and Early Testing

Restenosis after balloon angioplasty occurs secondary to multiple physiological reactions, including elastic recoil, negative remodelling and intimal hyperplasia, and drug-coated balloons appear to diminish all three reactions. To date, most clinical drug-coated balloon experience has occurred with paclitaxel. Paclitaxel appears to be optimal due to its lipophilic properties, short absorption time, and prolonged duration of antiproliferative effects.21 In animal models, paclitaxel-coated balloon dilation of 60 seconds released approximately 90 % of the drug from the balloon within the arterial wall. Using an animal model, when compared to a plain balloon, paclitaxel has demonstrated a 54 % decrease in late lumen loss.22,23 Contrasted with paclitaxel-coated stents, paclitaxel-coated balloons proved superior at inhibiting intimal hyperplasia.24 In another animal study, Cremers et al. demonstrated that most of the drug release occurs rapidly early in balloon inflation and neointima formation could not be decreased by inflating another drug-coated balloon in a previously treated area.25

Technology Review

To gain an understanding of the potential in this vascular bed, let us review what is known about the science of drug-coated balloons. Currently, standard balloon catheters are covered with the drug–excipient combination. The main theoretical goal would be to fully maintain an antiproliferative agent on a balloon until it is positioned at the lesion and then have all of the intended dose leave the balloon and reside completely within the targeted tissue, with little if any systemic loss. Current technology has fallen short on many of these goals. The current approach uses a combination of antiproliferative agent and an excipient in a crystalline form that once in the intima maintains a ‘micro-depot’ for the antiproliferative to diffuse into the tissue for a prolonged period of time.26 The currently used antiproliferative is paclitaxel in a dose ranging from 2 to 3 μg/mm. The challenge will be to apply the drug mixture to the balloon surface and obtain uniform distribution with minimal loss during packing, sterilisation, shipping and handling. While most of the data for drug-coated balloons currently relate to paclitaxel, the ‘limus’ family of agents may also be suitable; however, this family of drugs may not diffuse into media and adventitia or maintain tissue concentrations for as long as is necessary to treat this disease process. A number of excipients have been used, such as iopromide, urea, polymers and nanoparticles. Typical balloon inflations are 30–60 seconds. The majority of the drug is released downstream, with 10–15 % of the total drug located in the wall 40–60 minutes later. Approximately 10 % (one-hundredth of the initial balloon dose) will still be present at the treatment site 24 hours later.27

Drug-coated Balloon Clinical Use

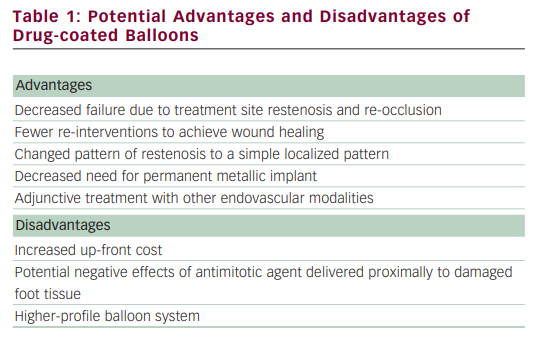

There is recently increasing enthusiasm for the use of PTA with balloons coated with anti-restenosis agents. This enthusiasm stems from the results of two randomised superficial femoral artery (SFA) trial publications using balloon catheters coated with paclitaxel, demonstrating encouraging results when compared with uncoated balloons. However, most technologies can be associated with advantages and disadvantages (see Table 1). In the Local taxan with short time exposure for reduction of restenosis in distal arteries (THUNDER) trial, 154 patients were randomly assigned to one of three strategies: bare balloon, bare balloon with paclitaxel dissolved in contrast media, and a paclitaxel-coated balloon. The late lumen loss was significantly lower in the segments treated with the coated balloon for mean lesion lengths of 7.5 cm.28 In a second study, 87 patients were randomised to bare balloon versus paclitaxel-coated balloon, and in mean lesion lengths ranging from 5.7 to 6.1 cm, late lumen loss and target lesion revascularisation were significantly lower in the coated balloon-treated segments.29 Whether this type of sustained restenosis reduction will be seen in the infrapopliteal vascular bed has yet to be determined. Infrapopliteal use of drug-coated balloons is an exciting proposition. However, there are some nuances to drug-coated balloons that make evaluation important. As noted previously, current drug-coated balloons are associated with a significant amount of downstream drug delivery. Any possible effect of this downstream cytotoxic agent dosing on ulcers or infection will require evaluation. Tibial disease is not the same disease process as seen in the SFA or coronaries. Tibial disease is, pathologically, more a medial disease, associated with a very high prevalence of calcification that could theoretically affect the diffusion of the drug into the media and adventitia.30 To date there has been only one publication on the use of a drug-coated balloon in the infrapopliteal segment. Schmidt et al.31 treated 104 patients and 109 limbs for CLI (82.6 %) or severe claudication (17.4 %). Tibial disease was complex, with a mean lesion length of 176 ± 88 mm. Angiography performed in 84 treated arteries at three months showed a restenosis rate of 27.4 % (19.1 % had restenosis of more than 50 %, and 8.3 % were occluded). When restenosis was identified, it was usually focal and did not typically affect the entire treated segment. Only in 9.5 % of all angiographically evaluated arteries was the entire treated segment restenosed or re-occluded. During a follow-up period of 378 ± 65 days, one patient was lost and 17 died. Of the 91 limbs remaining in the analysis, clinical improvement was present in 83 (91.2 %). Complete wound healing occurred in 74.2 %, whereas major amputation occurred in four patients, resulting in limb salvage of 95.6 % for patients with CLI. Trial design for infrapopliteal approval of drug-coated balloons in the US will be complex. As noted in the BASIL trial and a recent large meta-analysis comparing plain PTA with surgery, patency was improved with bypass but amputation-free survival was not significantly different up to three years later. This lack of differentiation may be due to multiple factors, including the shorter-term need to provide improved perfusion as well as the high mortality rate in these patients. The recently presented self-expanding tibial stent multicentre trial, the Xpert™ stent study for chronic critical limb ischemia (EXCEL), evaluated several clinical endpoints that may be important, such as wound healing rates and time to healing.32 Other key variables that may need evaluation include time to ambulation and maintenance of independent living status. Patient selection may also be important. Both the EXCEL and the Preventing amputations using drug eluting stents (PARADISE) trials illustrated that Rutherford scale 4 and 5 patients survive longer and have higher limb salvage rates than Rutherford scale 6 patients.

Summary

Drug-coated balloon technology offers the potential for providing an efficacious, cost-effective treatment platform for the infrapopliteal vasculature. Even if the longer-term patency does not match the data from the SFA, perfusion optimised for a longer period of time may allow CLI to be treated with fewer repeat procedures. Sophisticated trial designs may allow for less burdensome enrolment, so that this technology, which is available worldwide, may also be offered to our patients in the US.