Transcatheter mitral valve repair (TMVr) with the MitraClip is an effective therapy for mitral regurgitation. Several trials have demonstrated improved survival in appropriate patients and similar survival rates compared with surgical mitral valve repair.1,2 Not only does MitraClip improve survival compared with medical therapy alone, but it also provides a large improvement in quality of life, as demonstrated by less frequent hospitalizations for heart failure and improvements in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire scores.3,4 This correlates with improvements in New York Heart Association (NYHA) heart failure classification and other tangible measures, such as 6 minute walk distances, along with physiological changes, such as less regurgitant volume and reductions in left ventricular volume and left atrial size.5,6

MitraClip has been commercially available in the US as an alternative to surgical mitral repair for primary (degenerative) mitral regurgitation in patients at high risk of complications related to surgery since 2013, after the publication of the EVEREST II results and the EVEREST high-risk registry.2,7 The device was approved for use in patients with severe secondary (functional) mitral regurgitation in March 2019 following the results of the COAPT trial.1 With increasing MitraClip use, real-world data have shown >90% procedural success, defined as a reduction in residual mitral regurgitation to ≤2+ and freedom from mortality or cardiac surgery.8–10 Optimal results have further been defined as ≤1+ residual regurgitation, which correlates with improved outcomes such as increased survival and decreased heart failure hospitalizations.6

Although TMVr is a novel therapeutic option for patients, it remains a technically challenging procedure that requires collaboration between multidisciplinary specialists for both patient selection and device deployment. The operator is required to manipulate the device through a precise transseptal puncture and meticulously traverse the complex mitral apparatus under echocardiographic guidance for successful positioning to grasp the anterior and posterior leaflets of the mitral valve while the heart is beating. Minute adjustments in clip position can have a considerable effect on procedural results, and imaging of the clip and the mitral valve leaflets, as well as assessment of residual mitral regurgitation, can be challenging. Typically, discussions between multiple team members occur prior to clip deployment to ensure optimal results. Fortunately, despite the complexity of the procedure, complication rates have remained acceptably low, but serious adverse events still occur in up to 3% of procedures.9

Optimizing outcomes for patients remains a priority for providers, and therefore the relationship between experience and clinical outcomes, which has been apparent across procedurally based medical fields, is of great interest. However, the number of procedures performed does not simply explain this phenomenon. Rather, clinical judgment, decision making, and proper patient selection are all thought to have important roles.

In the surgical literature, higher procedural volumes have been associated with improved outcomes, particularly in intricate pancreatic resections and esophagectomies.11 Complex cardiovascular surgeries are no different, where both septal myectomies and mitral valve repair have improved clinical outcomes when performed by experienced surgeons. For example, complication rates for both ventricular septal myectomy and alcohol septal ablation, particularly the need for postoperative pacemakers, were nearly half at high-volume centers compared with the nationwide average.12,13 Similarly, surgeons who perform more than 20 surgical mitral valve repairs per year have superior clinical outcomes and repair durability.14 The volume–outcome relationship has been studied throughout interventional cardiology, from complex coronary intervention to newer areas of structural cardiology, particularly transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).12,15 Hospitals where more than 20 TAVRs per year were performed had shorter hospitalizations, lower cost of the procedure, and decreased in-hospital mortality.15 Similarly, a large case experience with unprotected left main percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI; >15 procedures per year) has been shown to result in an 80% reduction in major adverse cardiovascular outcomes at 1 year.16 The overarching trend is that clinical outcomes improve with experience, and it stands to reason that experience may be more important for more complex procedures.

Current Literature

Early studies were published reporting single-center experiences with MitraClip with results similar to clinical trials, achieving <2+ mitral regurgitation and acceptable rates of complications.17,18 As MitraClip became commercially available, investigators evaluated the efficacy of the device in the real world.8 Procedural success remained >90%, with rates of 30-day mortality <6%, consistent with the EVEREST II trial.2 As greater experience was gained, the efficacy remained consistent and in-hospital complications decreased.9 Concomitantly, investigators began reporting their procedural results with increasing familiarity of the device, and detailing improved case selection and procedural characteristics that led to improved outcomes.8,19,20

The Mayo Clinic reported procedural details of their first 75 cases and placed them in sequential cohorts (Cases 1–25, 26–50, and 51–75). In the third tertile of case experience, time to first clip delivery and fluoroscopy time were shorter and complication rates were lower compared with the first and second tertiles of experience.19 Data from Germany showed a marked decrease in procedure duration despite an increasing number of clips deployed and a shorter length of stay as experience increased over 126 cases.20 The procedure success, heart failure classification, and rates of major adverse cardiac events in short term follow-up were similar among early procedures in both studies. European cohorts had similar results to the early US operators in terms of residual regurgitation and mortality as early experience increased.10,21,22

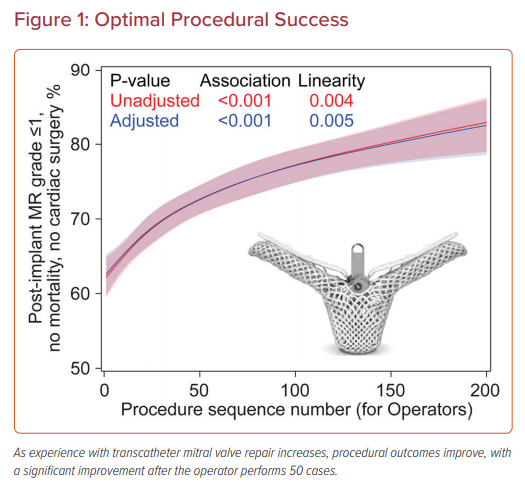

Two larger studies using data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) and American College of Cardiology (ACC) Transcatheter Valve Therapy (TVT) Registry have evaluated the relationship between experience and outcomes of TMVr with the MitraClip; the first study evaluated institutional experience and the second focused on individual operator experience (Figure 1).23,24 Procedures were categorized according to institutional or operator experience to examine the correlation with procedural success, procedure time, and complications. Procedural success was categorized as acceptable (≤2+ mitral residual regurgitation) and optimal (≤1+ mitral residual regurgitation) for the analyses. The mean STS predicted risk of mortality with mitral valve repair was >5% and the risk for mitral valve replacement was >8%. Most cases were performed electively for degenerative mitral regurgitation and a single MitraClip was deployed in most cases, predominantly in the A2–P2 position. Of note, sites and operators were more likely to perform urgent procedures and use more than one clip as experience increased.

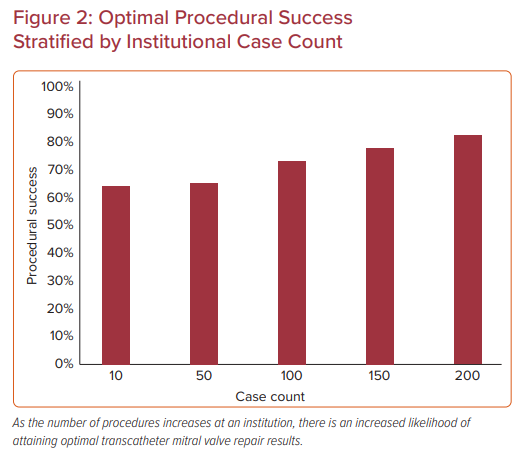

In the institutional analysis, institutions were categorized according to tertiles of case experience (1–18, 19–51, or ≥52 cases) and the median case experience was 30 cases (Figure 2).23 In all, 12,334 MitraClip procedures were evaluated at 275 US sites between 2013 and 2017. Most patients had degenerative mitral disease (86%) and NYHA Class III or IV symptoms (85%). Baseline characteristics across tertiles were relatively similar, with an STS predicted mortality risk of 5.9% for valve repair; however, in the third tertile of case experience, patients had higher prevalence of functional regurgitation, hypertension, leaflet calcification, and less mitral stenosis. Procedural success was achieved in >91% of all procedures, but ‘optimal’ procedure success increased from 62% to 65.5% to 72.5% with increasing institutional experience.

Along with improved results, average procedure time decreased by 45 minutes across the three groups, despite more clips deployed per case (46% versus 38% with ≥2 clips). Although an inflection point was present at approximately 50 cases in these learning curves, procedural results continued to improve out to greater than 150 procedures, suggesting that the learning curve for the procedure is longer than may have been thought. However, after an adjusted analysis of baseline patient variables, the relationship between experience and procedural success was no longer significant, which suggests that case selection was an important factor in these results.

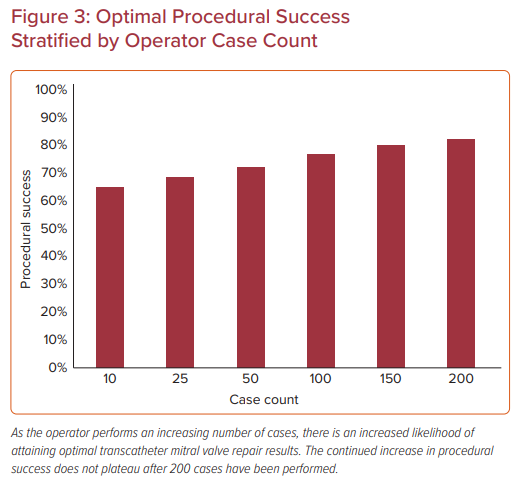

Similar results were demonstrated in another analysis of the STS/ACC TVT Registry, which stratified 14,923 procedures among 562 operators according to MitraClip case experience.24 Procedures were categorized based on the operator’s case experience at the time of the procedure (<25, 25–50, or >50 MitraClip procedures). In the case of two operators performing the procedure together, the procedure was categorized based on the operator with the greater case experience. Again, most cases were for 3+ or 4+ mitral regurgitation (93%) with degenerative disease (86%) in the elective setting (87%) primarily treated with one clip (53%). Baseline characteristics differed in that more experienced operators were less likely to treat patients on home oxygen or with pre-existing mitral stenosis and more likely to treat unstable patients and place an atrial septal defect closure device at the conclusion of the case. Increasing operator experience was associated with a modest improvement in procedural success (from 91% in the first 25 cases to 93.8% for ≥50 cases).

The association between operator experience and ‘optimal’ procedure success was greater, increasing from 63% to 68% to 75% across the tertiles of experience.24 Procedure time also decreased as operators gained more experience, similar to the site-level analysis. These associations remained significant following adjustment for patient characteristics, suggesting that the improvement in outcomes observed with increasing operator experience cannot be attributed solely to case selection. To further investigate site influence on operator outcomes, a sensitivity analysis was performed to examine outcomes for early experienced operators (≤13 procedures) practicing at more experienced and less experienced centers. This revealed there were no significant differences in procedure success, time, and complications associated with site experience (Figure 3).

In both studies, complication rates decreased with increasing experience at both the institutional and individual operator level.23,24 When examining the institutional experience, complications rates were 13.6%, 12.0%, 11.5% in the lowest to highest tertile of case experience, respectively. The reduction in complications was driven by fewer vascular access and bleeding complications and fewer single-leaflet device attachments, whereas stroke, transseptal puncture complications, and mortality did not differ among the groups. Complication rates decreased from 9.7% to 8% to 7% with increasing operator experience, but again this was not driven by mortality, stroke, or transseptal complications.

The take-home message from these two studies is that both institutional and operator experiences play a role in procedural outcomes of TMVr with MitraClip. As mentioned previously, achieving optimal results from mitral repair with ≤1+ residual regurgitation is beneficial and the ability to attain these results correlates with experience; however, it is important to remember that the learning curve for the procedure does not appear to plateau even as the operators approach a 150-case experience. Different institutions and operators began their experience at different time points, therefore one explanation for this phenomenon is early high-volume operators have continued to adopt new techniques and further optimize their results.

The knowledge base for procedural planning and technical aspects of MitraClip has continued to expand and improve as the utilization of the device increases. One example of this, which led to a significant change in procedural outcomes, was the implementation of continuous left atrial pressure assessment and monitoring, which was not routinely performed in early MitraClip procedures but has since been widely adopted as an integral aspect of decision making during the procedure. Achieving optimal echocardiographic and hemodynamic results is correlated with improved clinical outcomes.25–27 In addition, the device is now in its fourth iteration, with two clip sizes available to better accommodate individual pathology. Although the above studies did not evaluate which generation of the device was used, improvements in the technology likely also contributed to enhanced procedural results.

Another crucial aspect of the MitraClip procedure is optimal echocardiographic imaging not only for device manipulation and deployment, but also for patient selection. The experience of the echocardiographer, which contributed significantly to the institutional experience in the studies above, greatly affects the initial transesophageal study. It has been demonstrated that preprocedural imaging can predict procedural outcomes, particularly the presence of a single jet, flail leaflet, and high-quality three dimensional imaging.28 Another important echocardiographic marker for improved clinical results is the ability to place the clip in the A2–P2 position.8 Having an echocardiographer who understands these data and can perform the diagnostic study with these criteria in mind is invaluable in selecting patients in whom an optimal result can likely be achieved.

Given these data, it appears important for less experienced operators to understand their position on the learning curve for the procedure, and to pay particular attention to case selection in their early experience. With the inflection points for improved outcomes and decreased complication rates occurring at approximately 50 cases, it has been suggested that a reasonable target for procedural cadence is two or more procedures per month, in which an operator could achieve an experience of 50 cases within approximately 2 years. In addition, it would seem worthwhile for new operators early in their experience of TMVr with MitraClip to pair themselves with a more experienced operator and echocardiographer to assist in the clinical judgment of an adequate result during the procedure.

Future Horizons

The frontier for transcatheter mitral valve interventions remains broad given the complexity of the valve apparatus, multiple modes of valve failure, and variability of patient anatomy. Currently, TMVr with MitraClip is the only transcatheter mitral therapy approved in the US. Operators are becoming increasingly familiar with the device and excellent results are being attained, but mitral repair is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Many novel transcatheter therapies are being developed beyond edge-to-edge repair, ranging from annuloplasty technology to ring and repair combinations and to numerous valve replacement devices. Proper patient selection has already proven to be correlated with clinical outcomes, as detailed in the studies discussed above, and will remain important but, as the structural cardiologist’s toolbox expands, proper device and patient selection will both be imperative.

New therapies will likely also be associated with a learning curve, and further research will need to detail these early experiences. As additional valve therapies become available, the number of MitraClip procedures could decline; if so, the volume–outcome relationships and less utilization of the procedure may be even more important to consider.

As the field of mitral valve therapy continues to evolve, further research will be necessary into how best to select and treat our patients with the multitude of transcatheter therapies available.