The incidence of AF is on the rise.1–3 This is secondary not only to increasing prevalence but also a focus on increased recognition of occult AF for primary thromboembolic (TE) prevention.4 How we identify and treat these patients with AF is constantly in flux. While it is possible that a novel procedure or antiarrhythmic drug could create sweeping changes in AF management overnight, here we will focus on where we believe the most predictable changes in the approach to AF will occur in the near future.

Personal, Everyday Monitoring

We expect widespread advances in the area of mobile cardiac telemetry. Many currently available monitors are bulky and inconvenient, with some requiring removal for routine daily activities and others sometimes causing skin irritation that may result in low patient adherence rates.5 We expect current monitors will be replaced by personally owned and operated smart devices. Devices such as the Apple Watch™ (Apple Inc.) running apps like Cardiogram™ (Cardiogram) currently have the capability of identifying AF with sensitivity and specificity of 98% and 90%, respectively, against reference 12-lead electrocardiography in patients undergoing cardioversion.6 Ambulatory results, while not as promising, with improvement may revolutionize the way we use ambulatory monitoring.6 We predict these devices will cause a significant increase in the identification of occult AF. This will lead to an increase in the overall incidence of AF, perhaps temporarily increasing healthcare costs. However, a resultant decline in population-wide embolic cerebrovascular events with appropriate anticoagulant treatment may lead to a long-term overall decrease in costs for the healthcare system.

Technological advancements in this area will likely also extend to embedded rhythm monitors such as pacemakers and implanted loop recorders. With improvement in wireless communication, a patient may be able to routinely trigger rhythm recording from their implanted devices if or when they have symptoms. This could potentially identify rhythms that were under-detected because of lower rates or duration as well as providing reassurance in the case of normal rhythm findings. With the amount of data collected from these devices, we may even be able to clarify the temporal relationship between paroxysms of AF and embolic events leading to a treatment strategy that may limit the lifelong, continuous use of systemic anticoagulation with all of its inherent risks.4,7,8 We believe growth in personally owned devices capable of ambulatory rhythm monitoring will be exponential and practice changing.

The Role of MRI

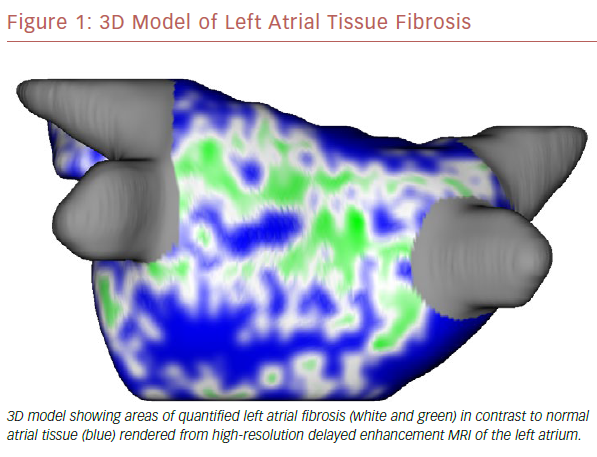

The use of cardiac MRI (CMR) in the management of AF is becoming standard of care at some large electrophysiology centers. It has the ability to quantify myocardial morphology, function and structure with high spatial and temporal resolution.9 In addition, it can identify areas of scar, or fibrosis, which may provide the substrate for developing and maintaining AF (Figure 1).10,11 It has been shown that tissue fibrosis, estimated by delayed enhancement MRI, is independently associated with the likelihood of recurrent atrial arrhythmia after the ablation procedure.12 There is ongoing investigation into whether targeted catheter ablation in areas of fibrosis in addition to standard pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) will result in improved procedural success rates (efficacy of DE-MRI-guided ablation versus Conventional catheter Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation [DECAAF-II; NCT02529319). If the DECAAF-II study is positive or another treatment modality is found more effective, than standard ablation techniques, randomized controlled trials will need to be repeated comparing it against current medical therapies.

The degree of atrial fibrosis as seen on CMR has also shown to be associated with increased major cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event risk, primarily as a result of an increase in transient ischemic attack/stroke.13 Currently no imaging parameter of the left atrium is part of the risk scoring system. Atrial fibrosis and other left atrial parameters may be used in the future to guide the use of systemic anticoagulation independent from or in addition to the CHADS2-VASc score.14 If we can predict the ideal candidate for an ablation procedure based on objective myocardial-based substrate findings, we could restrict potential complications only to patients who may derive the most benefit.

Substrate Modification

Catheter ablation is currently the most commonly used invasive technique to modulate the cardiac electrical system in AF. Developed in the early 2000s, the success rate of current PVI catheter ablation procedures are modest at best, with only approximately half of patients having 2-year of freedom from arrhythmia.15 Targeted ablation strategies such as roof lines and complex fractionated electrogram ablations have not shown significant improvement in addition to the standard PVI technique.16–19 One promising alternative lies in uniting CMR findings with targeted ablation techniques such as fibrosis- or substrate-guided ablation mentioned previously.9 Other less invasive strategies such as external stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) may have a role in the treatment of AF in the future. Despite being in its very preliminary stages, SBRT has been shown to be effective in the treatment of ventricular tachycardia in heart failure patients as well as being capable of non-invasive atrio-ventricular node ablation.20–22 While it is recognized that left atrial substrate is notably different from even the right atrium, it is reasonable that advances in SBRT could make this feasible.23,24 This is especially promising in high-risk individuals who are poor candidates for invasive procedures.

Population-based Care

It is well recognized that different populations have variable response to treatment of AF.25 Recently, for example, the Catheter Ablation versus Standard conventional Treatment in patients with LEft ventricular dysfunction and Atrial Fibrillation (CASTLE-AF) trial demonstrated that patients with symptomatic congestive heart failure with ejection fraction <35% obtain mortality benefit and reduction in heart failure hospitalizations with catheter ablation.26 This was also suggested in the intention-to-treat primary endpoint (all cause mortality, disabling stroke, serious bleeding, cardiac arrest) sub-group analysis of not only heart failure patients, but also patients aged <65 years and those in minority populations in the Catheter ABlation versus ANtiarrhythmic drug therapy for Atrial fibrillation (CABANA) trial.27 Catheter ablation is now a Class IIB recommendation in those with systolic heart failure.28 So should we be ablating all patients with AF and systolic heart failure? The answer still seems unclear as both CABANA and CASTLE-AF had limitations such as significant treatment group crossover and high use of amiodarone. We need more data, but based on these trials we predict there will be more evidence available for early use of catheter ablation techniques in heart failure and other yet-to-be-determined patient populations.

Anticoagulation and Left Atrial Appendage Modification

Anticoagulation to reduce TE risk is currently the only widely accepted prognostic intervention in AF, therefore appropriate and judicious use is an important area of improvement.29 The widespread use of oral anticoagulation (OAC) including direct OACs and vitamin K antagonists, while significantly decreasing the risk of TE events, conversely confers a significant increase in bleeding of around 2–4% annually and contraindications to these drugs leaves a large population of untreated patients at risk.29–34

Atrial appendage occlusion is a developing area of innovation in AF management, particularly in those patients unable to tolerate long-term anticoagulation.35,36 Most recently this has been shown to have benefits beyond reduction in TE risk, improving success rates of catheter ablation in addition to standard ablation procedures.37,38 Unfortunately these devices come with a complication rate as high as 5–10% in some studies, although this seems to improve with operator experience.35,36 The question of whether these devices should only be used in those with a contraindication to OAC or implanted when patients are at low embolic risk but able to take OAC temporarily in order to reduce a lifetime dependence on OAC will likely be answered in the next few years, as will long-term complications – if any – of these devices.

The Story of Modifiable Risk and a Healthier Future

AF is strongly attributable to modifiable risk factors such as obesity and substance abuse; therefore, the prevalence of AF is largely tied to the incidence of these risk factors.39–41 In recent decades there has been a steady incline in the rate of obesity, rising nearly 10% in adults aged >20 years from the late 1990s to the early 2010s.42

For the first time, the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society task force has included weight loss in the guidelines for AF management.28 There is strong evidence to include risk-factor modification in the guidelines. Obesity rates and subsequent peri/epicardial fat have been found to correlate with the degree of atrial fibrosis – a known surrogate for AF and success of AF ablation.43,44 It is also known that weight loss and exercise can dramatically change cardiac structure and lower AF burden in these obese patients.45–48 Therefore, obesity rates are an important marker of the future global impact of AF. If obesity rates continue to rise, rates of AF will rise concordantly. Coupled with an aging population, the healthcare burden of AF will continue to be an important expenditure in the next decade.

Cigarette use in the US, another known risk factor for AF, is generally stable or declining.49,50 How the use of nicotine vaping – which is increasingly common especially in teenagers – will affect the prevalence of AF and other cigarette-related conditions is not well understood.50

We anticipate that clinically guided risk-factor modification will become increasingly important over the next decade, with payment potentially linked to these goals. In the most extreme scenario, perhaps similar to bariatric surgery, successfully demonstrated weight loss and tobacco cessation will be required before procedures with the potential for complications and poorer predicted success rates are reimbursed. This could make modifiable risk factors a target of contention between payers and healthcare providers in the near future.

Conclusion

There is abundant opportunity for the advancement of AF care. Given the current epidemic of atrial arrhythmia and the associated healthcare costs, we expect significant continued advancement in AF identification, risk stratification, and treatment.51 It is possible that new technologies such as the collimated ultrasound ablation system or painless optogenetic defibrillation techniques could change practice overnight.52–55 However, for now the narrative remains: rhythm or rate, ablate or medicate. These questions will hopefully be answered clearly in the coming years or reimbursement for costly and potentially hazardous procedures is at risk.