Cardiac tumors are a relatively rare phenomenon, and most of these are benign. However, given their location, most require prompt surgical treatment as the sequelae of such tumors can be catastrophic. Myxomas constitute about 50% of benign intracardiac tumors and can be particularly large, often nearly obliterating the cavity of the heart that they originate from. Particularly large tumors can cause mass effect on the cardiac chamber, as well as marked hemodynamic derangement including secondary pulmonary hypertension which complicates the surgical management. We present an interesting case of a cardiac myxoma with associated severe pulmonary hypertension requiring careful hemodynamic optimization prior to surgical removal.

Case Presentation

A 41-year-old man without significant cardiac history presented with abdominal pain, bloating, and dyspnea for the past month. His symptoms were associated with an 18 lb weight gain, bilateral lower extremity edema, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and three-pillow orthopnea. Recently, he noted feeling pre-syncopal when lifting boxes and while coughing. On further questioning, the patient noted two prior episodes of right upper extremity and left lower extremity paresthesia and paralysis over the past year; both resolved spontaneously. Prior to this, he was an active individual with unlimited exercise tolerance and was able to do a significant amount of walking and lifting for his job. He denied any recent symptoms.

The patient’s medical history was notable for a one-pack-per-day smoking history for the past 25 years. He also smoked marijuana occasionally. He had not attended primary care for the past two decades.

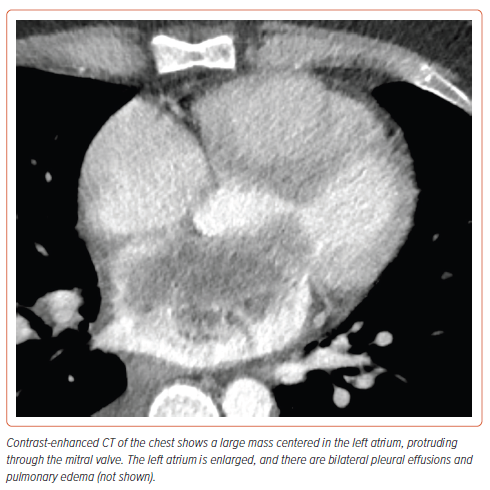

He presented to the emergency department for further evaluation. Given his abdominal distension and bloating, a CT scan of the abdomen was performed, which showed signs of volume overload, with pleural and pericardial effusions, small-volume ascites, and abdominal wall edema. A CT of the chest revealed an 8.5 cm mass originating in the left atrium, prolapsing through the mitral valve causing near-cavity obliteration of the atrium (Figure 1). A 1 cm right lower lung lobe indeterminate mass was also identified.

Differential Diagnosis

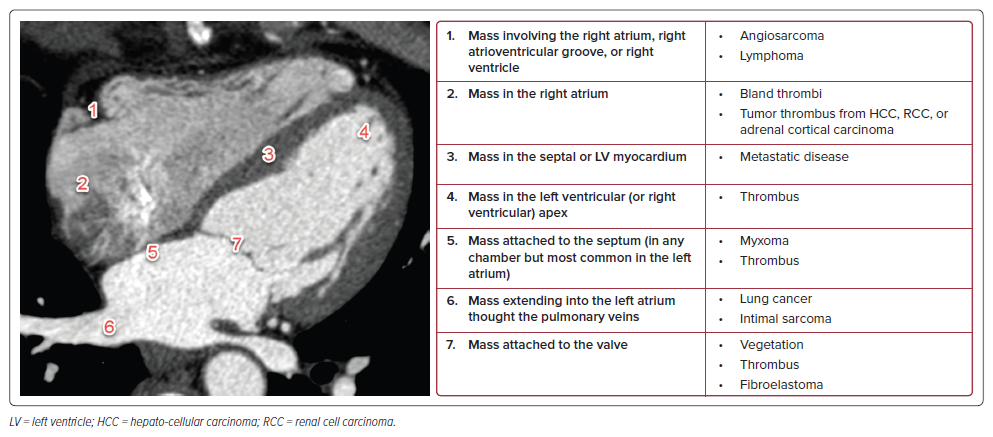

The differential diagnosis for an intracardiac mass is broad, including both benign and malignant tumors, as well as intracardiac thrombi.1 The patient’s age and the location of the mass are key in narrowing the differential (Figure 2).

In our case, the initial chest CT demonstrated a large mass centered in the left atrium, abutting the intraventricular septum, and extending through the mitral valve. Given the location, three main entities were initially considered: thrombus, metastatic disease, and atrial myxoma.

Thrombi are the most encountered intracardiac masses and should be considered when the mass is located within a cardiac chamber. This is especially true when the chamber is dilated and may be predisposed to slow flow or areas of stasis (e.g. a dilated left atrium, left ventricular aneurysm, etc.). On CT they can appear like myxomas, but on MRI they will not enhance and often will be T2 hypointense.

Metastatic disease is the most encountered neoplastic process involving the heart. In particular, lung cancer can extend into the left atrium by growing through the pulmonary veins. This was considered in our case, but ultimately ruled out as all the pulmonary veins were patent. On cardiac MRI (cMRI), metastatic disease will be T2 intermediate and will enhance.

Myxomas can occur in any cardiac chamber, but are most common in the left atrium. They are mobile, T2 hyperintense on cMRI, and always attached to the septum, regardless of which chamber they arise in. They are the most encountered benign neoplasm of the heart.

Initial Workup

Laboratory results were notable for markedly elevated N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (>11,000 pg/ml), mild elevation of transaminases (alanine aminotransferase 225 U/l, aspartate aminotransferase 106 U/l, alkaline phosphatase 146 U/l), a normal lactate, and an elevated C-reactive protein (40.4 mg/dl). Serial high-sensitivity troponins were just above the upper limit of normal. The rest of his basic laboratory results were within normal limits.

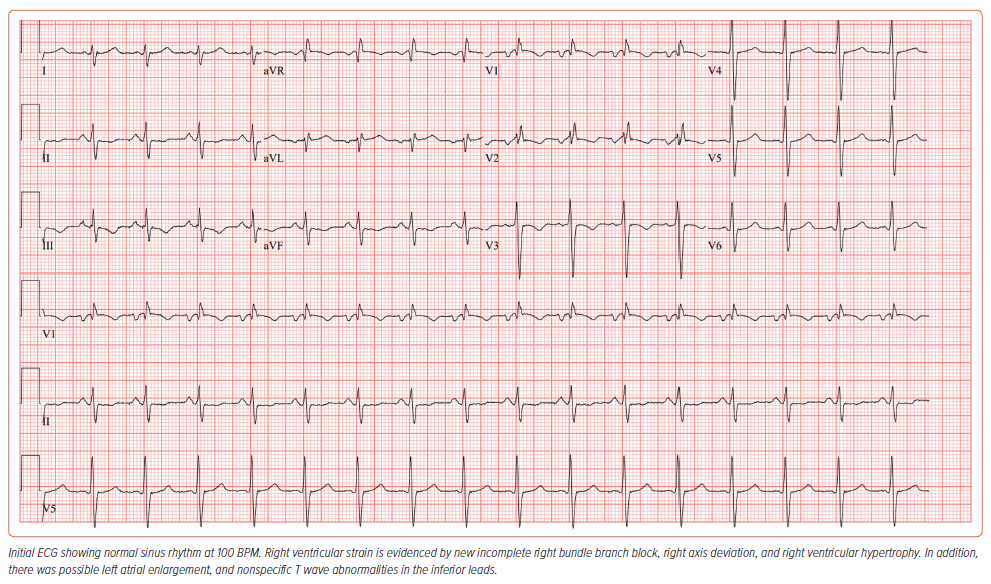

An ECG revealed normal sinus rhythm, with an incomplete right bundle branch block, and right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy (Figure 3). There was possible left atrial enlargement, and nonspecific T wave abnormalities in the inferior leads.

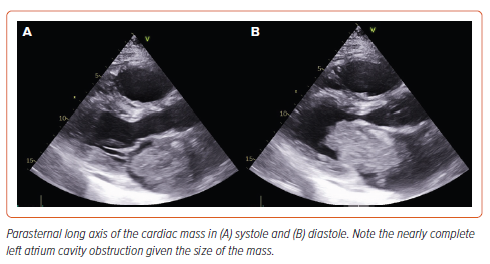

A transthoracic echocardiogram showed a 9.2 × 4.6 cm left atrial mass protruding into the left ventricle, with associated mild/moderate mitral regurgitation. There was severe RV enlargement and dysfunction with septal flattening. There was a mean mitral gradient of 10 mmHg and evidence of severe pulmonary hypertension, with an estimated pulmonary artery (PA) systolic pressure of 82 mmHg (Figure 4 and Supplementary Video 1).

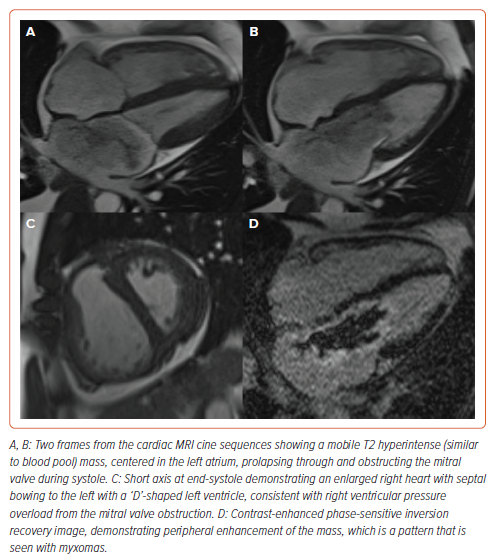

A cMRI revealed a peripherally enhancing, T2 hyperintense mobile left atrial mass attached to the interatrial septum, with prolapse through the mitral valve and associated moderate mitral regurgitation. These findings were strongly suggestive of atrial myxoma.2 In addition, the cMRI revealed signs of RV pressure overload (Figure 5 and Supplementary Video 2).

Given the patient’s smoking history and presence of right lung mass, a PET scan was obtained that ruled out fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the left atrial mass, but revealed a moderately hypermetabolic right lower lobe pulmonary nodule with surrounding ground glass opacity. There were minimally hypermetabolic right supraclavicular and scattered mediastinal lymph nodes that were favored to be reactive.

A CT head was performed because of a history suspicious of transient ischemic attack symptoms and revealed an age-indeterminant hypoattenuating lesion in the right caudate head, favored to represent an old lacunar infarct. For surgical planning, a coronary angiogram revealed moderate bridging of the left anterior descending artery, but no significant atherosclerotic coronary artery disease.

Management

Given the size and symptoms of decompensated RV failure with severe pulmonary hypertension, the patient was hemodynamically optimized before definitive surgical removal. He was started on empiric milrinone for inotropic support and pulmonary vasodilatation. He was then given gentle IV loop diuretics, given his symptoms of congestion, elevated jugular venous pulsation, and orthopnea. Lastly, he was started on systemic anticoagulation, based on his history of possible transient ischemic attacks as well as cMRI evidence of subtle thrombi lining the myxoma.

After a period of 48 hours, the patient was decongested and symptomatically feeling better. He was taken to the operating room on hospital day 3. An intraoperative transesophageal echo showed evidence of mitral stenosis as well as near-systemic PA pressures (PA 95/48 mmHg, blood pressure 106/82 mmHg) (Supplementary Video 3). After bicaval cannulation, initiation of cardiopulmonary bypass, cross-clamp, and cardioplegia, the left atrium was carefully opened in the interatrial groove. Direct examination confirmed an 8 cm mass attached to the left atrium between a right inferior pulmonary vein and the mitral annulus. The mass was shaved off its base, taking the endocardium with it (Figure 6). The base was then cryoablated at −60°C for 3 minutes. The atriotomy was closed, and separation from bypass was uneventful.

Pathologic analysis confirmed the diagnosis of atrial myxoma. His postoperative course was uneventful. A follow-up echocardiogram on post-surgical day 4 revealed mild RV cavity enlargement and moderate RV dysfunction. His PA systolic pressure was approximately 37 mmHg. He was discharged to home on post-surgical day 7.

Discussion

Primary cardiac tumors are rare and comprise 90% of all intracardiac tumors.3 Approximately 80% of these are benign; however, because of their location they do require surgical treatment.3 Myxomas constitute about 50% of benign intracardiac tumors. The majority of cardiac myxomas arise in the left atrium, and are usually pedunculated and attached to the endocardium by a stalk.4 While most are discovered incidentally or on autopsy, symptomatic presentations are related to mitral valve obstruction or embolic sequelae.5 Commonly presenting symptoms include dyspnea, orthopnea, fatigue, and constitutional symptoms. Obstruction of circulation by the myxoma can cause signs and symptoms of heart failure as well as acute pulmonary hypertension and RV failure for large masses that completely obliterate the left atrium (as in our case). Furthermore, direct pressure on the myocardium or conduction system can cause conduction disturbances including heart block and ventricular arrhythmias. Lastly, tiny thrombi on the surface of the myxoma or micro-fragments of the tumor can be released into the circulation, causing systemic embolic sequelae.

Common physical exam findings for large left-sided tumors include a mid-diastolic murmur, or ‘tumor-plop,’ as the mass transiently bounces through the mitral valve. Once the diagnosis has been made, prompt surgical resection is the standard of care to prevent the possibility of further embolic or cardiovascular events (such as those that occurred in our patient). In addition, hemodynamic stabilization with inotropic support may be required if the patient exhibits acute pulmonary hypertension. Long-term follow-up is needed with serial imaging as they have some tendency to recur.6

Depending on the location and size of the tumor, patients can have varied hemodynamic consequences. We used multiple imaging modalities (cMRI, transthoracic echocardiography, and transesophageal echocardiography) to confirm the diagnosis and guide management. All cardiologists should be able to recognize the impact of significant left-sided obstruction, including marked preload dependence, possible acute pulmonary hypertension, and mitral stenosis physiology.

Follow-up

The patient was seen in the cardiothoracic surgery clinic approximately 3 months after discharge. A follow-up PET was obtained for the right lower lobe lesion and revealed anatomic and metabolic resolution of the nodule, which was now thought to be secondary to an inflammatory process. The patient has returned to work and remains symptom free. Given the possibility of recurrence, follow-up examination, including serial imaging, should occur regularly.

Conclusion

The differential for left atrial mass remains broad, especially in the setting of patients with risk factors and imaging concerns for malignancy. However, multimodal imaging can be useful to secure a diagnosis, especially for atrial myxomas which have pathognomonic features on cMRI. Prompt medical and surgical attention is required, with particular emphasis on preoperative hemodynamic optimization for patients with pulmonary hypertension and impending RV failure, as in our patient, to prevent potentially catastrophic complications.