Gender and Sex Terminology

The term sex refers to biological constructs including genetic, anatomical, and hormonal characteristics. When referring to sex-related differences, we have used the categorization of male versus female. The term gender reflects social constructs, including roles, behaviors, and identities. When referring to gender-related differences, we have used the categorization of men versus women. For the purpose of this review, we have generally maintained the terminology used in the original articles referenced, but recognize that these terms may have been interchanged inappropriately in the referenced literature.

Chest pain is one of the most common reasons for emergency department visits.1 The term is used by patients to describe an uncomfortable sensation in the anterior chest. Chest pain that raises concern for myocardial ischemia is often reported as pressure, tightness, squeezing, or heaviness, and is occasionally associated with nausea, diaphoresis, or shortness of breath. Patients may also report pain or discomfort in an area other than the chest, including the shoulder, arm, neck, jaw, or upper abdomen.

The characteristic symptoms induced by myocardial ischemia have been historically described as typical versus atypical. Recently, the ACC/AHA Joint Committee on Clinical Data Standards defined chest pain and acute MI (AMI). The committee has discouraged the use of the term atypical, which can be used to describe both non-cardiac and cardiac symptoms that are not representative of myocardial ischemia.1 Instead, the multi-society committee has recommended the following terminology to describe chest pain: cardiac; possible cardiac; and non-cardiac.2

Presentation of Chest Pain in Women

Character, Timing, Location, and Associated Factors

Women with ischemic heart disease have a higher risk of dying of acute AMI than similarly aged men.3–5 Differences in symptom presentation among women is thought to play a role in treatment delays despite the burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in this population.

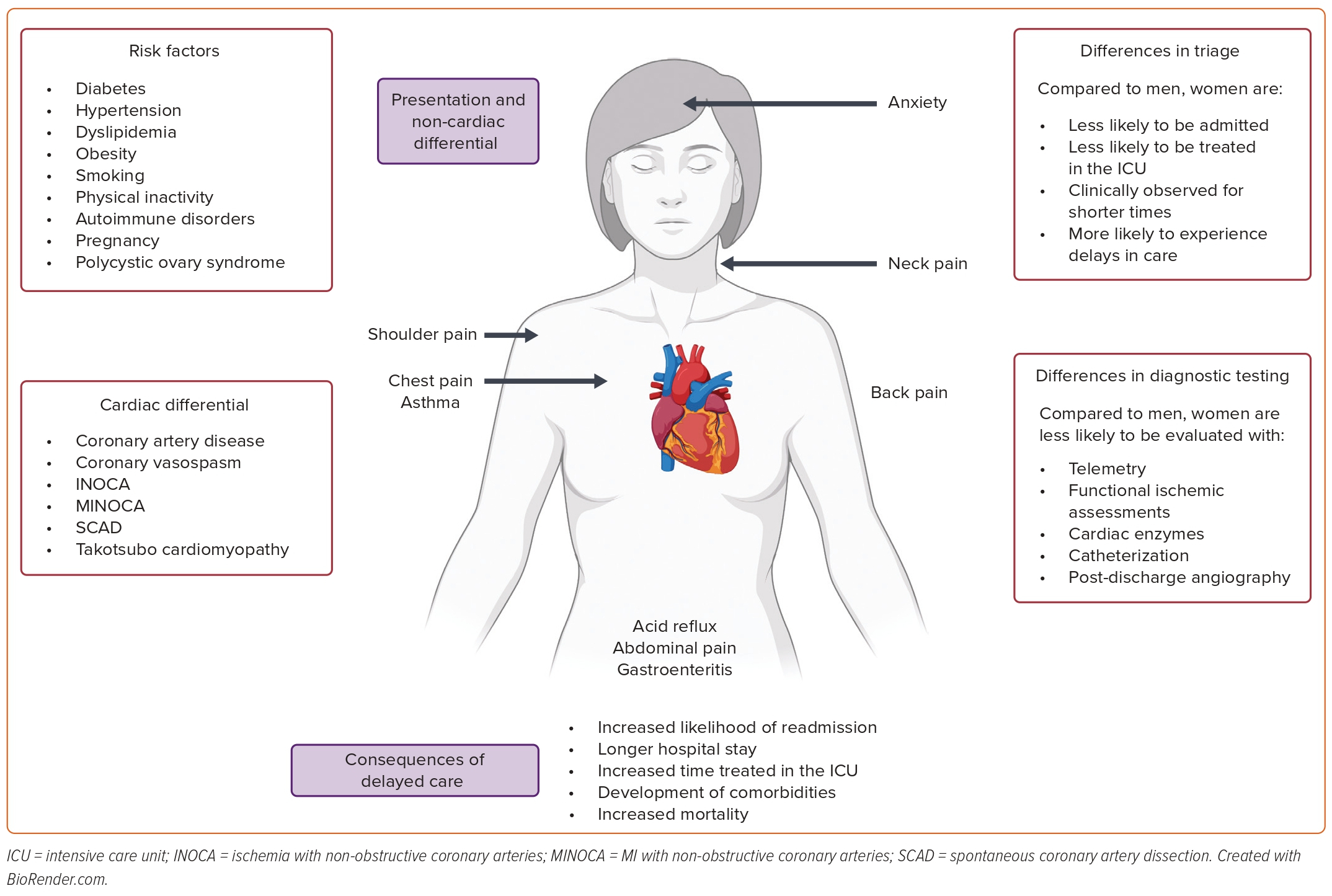

Most women present with traditional chest pain symptoms of pain, pressure, tightness, or discomfort.6–10 However, they are more likely than men to report a greater number of associated symptoms such as weakness and/or pain in the back, shoulder, or neck (Figure 1).10 Therefore, the patient’s complaint of several non-chest pain symptoms may influence the clinician’s decision to evaluate her ischemic heart disease, especially if chest pain is not the primary complaint at the time of presentation.11

The delays in diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in women illustrate the importance of thoughtful communication to health professionals and the public about not classifying symptoms in women as atypical and viewing symptoms in men as the gold standard.12

Most Common Risk Factors

Traditional CVD risk factors are similar in men and women, although prevalence and risk factors for chest pain differ by sex and gender.13

Risk factors, including diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, smoking, and physical inactivity, are either more prevalent or have greater effects in women compared to men.14 Young women who present with ACS are more likely to smoke and have a history of diabetes, metabolic syndrome, hypertension, or chronic kidney disease than young men.15,16 Women who experience MI often present with higher rates of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, elevated inflammatory markers, and poor mental health compared to men.16

Women have specific non-traditional cardiovascular risk factors because of their genetic and hormonal predisposition. They are at greater risk of developing autoimmune disorders than men, which may increase their risk of cardiovascular events.12 Patients with autoimmune disorders can develop endothelial damage and atherosclerosis over time, and autoimmune-related symptoms may overlap with clinical symptoms of CVD.17

Pregnancy itself poses risks to the cardiovascular health of women because of comorbidities that can develop during gestation, such as gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, and pre-eclampsia.12,18 Those with a history of adverse pregnancy outcomes are at risk of accelerated atherosclerosis and premature coronary artery disease (CAD).18

Women diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) may have dysregulation of hormones, including increased aldosterone (which can lead to an increase in blood pressure), a fall in estrogen, and increased androgens.17 Decreases in estrogen in women may lead to a loss of endothelium-derived nitric oxide, impairing vasodilation.19 Raised androgens may be related to insulin resistance and increases in visceral fat, although relationships to CV outcomes are ill defined.19

Most Common Diagnoses

Cardiovascular

Compared to men, women with chest pain are more likely to be diagnosed with coronary vasospasm, MI with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA), ischemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA), spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD), and takotsubo cardiomyopathy.20

Coronary vasospasm can be induced at the level of the epicardial coronary arteries or in the microvascular circulation of the heart.20 Coronary vasospasm is associated with MINOCA, defined as AMI without coronary artery obstruction on angiography.21 INOCA is defined by objective myocardial ischemia via abnormal EKG, imaging tests, or biomarker evidence, with <50% stenosis in the epicardial vessels.22 MINOCA and INOCA can be driven by vascular dysfunction and vasospasm in epicardial arteries or at the level of the cardiac microcirculation. Vascular dysfunction can lead to a supply–demand mismatch, leading to ischemia or infarction.22

SCAD is a dissection of an epicardial coronary artery not caused by atherosclerosis or trauma and accounts for about 35% of ACS in women.23 Notably, women make up 87–95% of SCAD cases and, while the exact mechanism is unknown, sex hormones may contribute to development of this condition.24

Women are less likely than men to have obstructive multivessel disease; however, this should not preclude this diagnosis from being thoroughly explored.23

Non-cardiovascular

Misdiagnosis of cardiac causes as non-cardiac in etiology seems to be more prevalent in women. Women themselves are likely to attribute their symptoms to a non-cardiac cause (particularly acid reflux and anxiety), which may contribute to delayed clinical presentation.25

Care-seeking behaviors of younger men and women hospitalized for AMI were described in the VIRGO study.10 VIRGO researchers found that women were more likely to have their symptoms initially attributed to a non-cardiac condition (53% versus 37%; p<0.001) by their provider, including acid reflux, stress and anxiety, muscle pain, asthma, diabetes, fatigue, or gastroenteritis.

Non-cardiac causes of chest pain that must be evaluated in women include pulmonary embolism, gastrointestinal disruptions such as esophagitis and peptic ulcer disease, pneumonia, pneumothorax, and costochondritis (Figure 1).2

Differences in Evaluation of Chest Pain in Women

Hospital and Intensive Care Admission

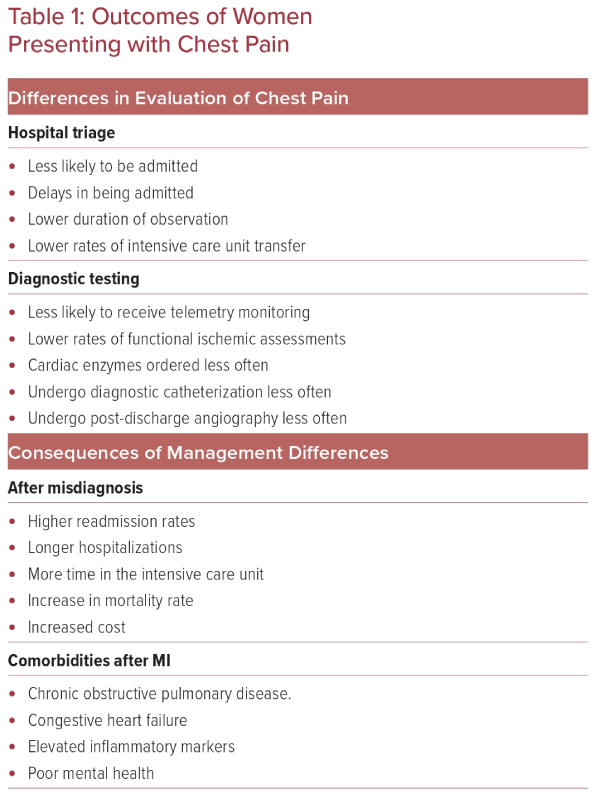

Women admitted to hospital after presentation with chest pain to an emergency department or ambulatory care facility experience sex- and gender-based differences in evaluation, hospital admission rates and management of their chest pain (Table 1).

A cohort analysis reviewing 54,134 patients presenting to an Alberta emergency department found that women presenting with stable angina, unstable angina, AMI, or chest pain were significantly more likely to be discharged than men.26 In 2010, a prospective German study of 1,249 patients similarly found that women presenting with chest pain were significantly less likely to be admitted to the hospital than men (2.9% versus 6.6%; p<0.01).27,28 Data from the BEACON trial further confirmed that women with suspected ACS were admitted to hospitals at significantly lower rates than men (33% versus 42%; p=0.04).29

The known lower incidence of obstructive CAD in women may contribute to this admission behavior; however, women found to have obstructive CAD have significantly higher mortality rates (RR 1.75; 95% CI [1.48–2.07]).30 Therefore, although less prevalent, there should be a high index of suspicion and appropriate evaluation for obstructive CAD in women, which may require increased rates of admission for further assessment.

In addition to differences in hospital admission rates, women experience lower rates of observation unit admission and delays in hospital admission, and are less likely to be transferred to an intensive care unit. A Swedish retrospective chart review of 2,393 patients found that women experienced a delay in hospital admission of 36 minutes on average compared to men, and men were three times as likely to be admitted to a coronary care unit.31 Other research, carried out in young adults, also found significantly decreased rates of hospital admission and rates of observation unit admission in women compared to men (p=0.026 and p<0.001, respectively).32

Diagnostic Testing and Imaging Studies:

Gender-specific differences also exist regarding diagnostic testing for women who seek care for acute chest pain. Given that women have worse outcomes after an AMI than men, it is important to evaluate cardiac causes of chest pain early and efficiently.33 However, significant disparities are present in performing early noninvasive testing.

In 2008, a study of 7,068 patients in the emergency department found that, over a span of 5 years (1995–2000), African-American women had a significant lower rates of chest radiography use over time (70.5–58.1%; p<0.05) compared to non-African-American women (76.1–77.4%). Non-African-American women had significantly less cardiac monitoring (53.1 to 42.1%, p<0.05) than non-African-American men (52.3–53.1%).34 These discrepancies were thought to be related to differences in insurance, provider bias, and atypical presentations of chest pain in certain groups.

Regarding patients with stable angina, women are also less likely to undergo a functional ischemia assessment than men, and, in women under 50 years of age, cardiac troponin (cTn) testing is ordered less frequently than in men (OR 0.78; 95% CI [0.70–0.87]).35,36

Gender-specific differences may be present in performing invasive cardiac testing and treatment, although studies have drawn varied conclusions.

In a large study of 7,272 patients presenting to an emergency department with chest pain, of those with cardiac troponin levels in the >99th percentile, women underwent 16% fewer diagnostic cardiac catheterizations than men (p<0.001).37 However, it should be noted that women were 11% less likely to be diagnosed with MI after catheterization.37

Post-hoc analysis of the CURE trial showed that women undergo in-hospital cardiac angiography less frequently than men (25.4% versus 29.5%; p=0.0001), and women also undergo post-discharge angiography less frequently (14% versus 16%; p=0.006).38

There are several plausible reasons for these differences in invasive testing rates, and various potential factors have been studied. Gender bias in invasive testing is likely to be not solely explained by differences in presentation, history, or clinical course.39 The disparity in cardiac catheterization does not appear to be related to physician sex.40 Women have also been shown to refuse invasive cardiac procedures at higher rates than men, which is likely to be one of many contributing factors to the disparities in observed invasive testing rates.41

Sex-specific physiologic differences have been implicated in the differing results of certain diagnostic tests. Clinicians should be aware of these sex-specific differences when performing and interpreting diagnostic results. Factors such as menopausal status and exercise capacity have been shown to affect the prevalence of CAD, EKG findings, and the accuracy of pharmacologic stress testing.42 Women are more likely to have elevated levels of brain natriuretic peptide and are less likely to have elevated levels of troponin when experiencing chest pain.43

Hospital Stay and Follow-up

Women hospitalized for cardiac chest pain have been shown to require longer inpatient stays and have different readmission patterns.

A study investigating patients who received inpatient phase I cardiac rehabilitation after AMI found that women had significantly more days of hospitalization, spent more time in the intensive care unit, and had a 4% higher 1-year mortality rate.44

In patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention for an ACS, being a woman has been shown to be an independent risk factor for 30-day readmission (13.0% women versus 9.6% men; p<0.0001).45

Another study has shown that young women (aged <65 years) have 30-day readmission rates that are nearly twice as high as those for men after acute an MI, and the reason for this is likely to be secondary to be non-cardiac causes.46

Further studies are needed to investigate sex- and gender-specific differences in hospitalizations for all-cause chest pain.

Cost and Economic Impact of Misdiagnosis in Women

Healthcare costs associated with heart disease in the US are greater than $200 billion annually.47 Given sex differences in the prevalence of atherosclerotic heart disease and usage of physician resources, women continue to face a high economic burden for all-cause chest pain.

In the 2006 National Institutes of Health-sponsored WISE study of 883 women, 5-year costs of $32,000 and $53,000 were associated with non-obstructive and three-vessel CAD, respectively. The predicted lifetime cost for an individual woman with recurrent, refractory chest pain without obstructive coronary disease has been estimated to be more than $750,000. The cost for women with obstructive disease was estimated to be roughly $1,000,000.48

Gender discrepancies that exist in the initial evaluation of chest pain contribute to further work-up and cost. A Spanish study of 41,828 women concluded that, upon initial evaluation, the diagnosis of AMI was underestimated in women presenting with chest pain leading to late and missed diagnosis, further elevating diagnostic costs.49

Future studies are also needed to comprehensively evaluate the differences between the cost of chest pain in men and women, as well as the economic impact of chest pain misdiagnosis in women.

Differences in Outcomes

Mortality and Morbidity

Women, especially those who are younger (aged <60–65 years), are commonly perceived to be protected from heart disease, and to have a higher likelihood of benign etiologies of chest pain. Oversimplification of this concept and overgeneralization regarding biological sex differences such as delayed atherosclerotic disease and stress manifestations lead to inappropriate dismissal and under-diagnosis of serious etiologies of chest pain in younger women.

This is exacerbated by the use of the dichotomous terms of typical/atypical chest pain as indicators of risk for cardiovascular events in women. We attempt below to dissect the factors contributing to differential outcomes of chest pain as an indicator of CVD in women, as well as the impact of worse cardiovascular outcomes on women’s mental health, which in itself is a predictor of cardiovascular health.

Hospitalization for chest pain is more often a predictor of CVD and mortality in men than women. In a study in Norway, women were less likely to have a cardiovascular diagnosis 1 year after discharge from the hospital with unexplained chest pain, and had lower mortality compared to men.50

Atherosclerotic burden is lower in women presenting with chest pain. In a study of patients with stable chest pain who underwent coronary CT angiography, women had a higher prevalence of atypical chest pain but lower overall CAD and all-cause mortality than men.51

Chest pain in patients with non-obstructive CAD can be due to etiologies that are more difficult to diagnose and treat because of difficulty in diagnosis and a lack of appropriate interventional and pharmacological therapies. This leads to higher morbidity rates, which disproportionately affect women, especially at younger ages. These etiologies include microvascular dysfunction leading to MINOCA, vascular spasm, and endothelial dysfunction.52 In particular, takotsubo cardiomyopathy is seen more often in menopausal than pre-menopausal women, but younger women with takotsubo syndrome have worse outcomes.53 Other non-atherosclerotic etiologies with worse outcomes in the acute setting that are more prevalent in younger women include SCAD.24

When chest pain is due to cardiovascular causes, women have worse outcomes even with prompt diagnosis. In a study of patients presenting with chest pain and stratified by cTn levels, women with cTn levels above the 99th percentile, which triggered a rapid cardiac evaluation, had higher 1-year rates of major adverse cardiovascular events than men. This was attributed to their lower use of appropriate medications and higher burden of comorbidities.37 In 2006, a study found that in patients without obstructive CAD on angiography, women with persistent chest pain at least 1 year after the procedure had more than double the rate of cardiovascular events compared to men.54

In the acute setting, outcomes of chest pain are also worse for women. In a retrospective study of all adults (over 50,000 patients) presenting to three emergency departments with chest pain over a 5-year period in Melbourne, Australia, women had a 35% higher likelihood of dying in the emergency department compared to men. Even though less likely to be admitted, women were also 36% more likely to die in the hospital if admitted.55

Age is an important factor in the disparities of outcomes between women and men, as these differences may become less pronounced in older populations. In a large observational study of patients diagnosed with MI, women aged >65 years were more likely to present with chest pain than younger women, and the difference in in-hospital mortality between men and women was attenuated by this age.9 Older women have had more favorable outcomes whereas younger women had higher mortality following AMI outside the acute setting after the initial 28-day period.56,57

The absence of chest pain on presentation with MI is a predictor of mortality risk for both sexes, but more strongly for women.58 Delay in diagnosis and treatment may not fully explain the higher morbidity after MI in women, since women also experience higher bleeding complications from procedures or drug therapies, and higher rates of developing mechanical complications such as heart failure.

Impact on Mental Health

The prevalence of depression after MI, a known adverse prognostic factor following ACS, and anxiety are higher in women compared to men.59 Following adverse cardiovascular events such as MI, women survivors aged <50 years old are also more susceptible to subsequent ischemia induced by psychosocial stress.60 Women with atherosclerotic CVD report poorer interaction with providers, and perception of health and quality of life compared to men.61

Mechanisms of Differences in Presentation and Outcomes

Bias and Impact of Physician Sex on Testing and Outcomes

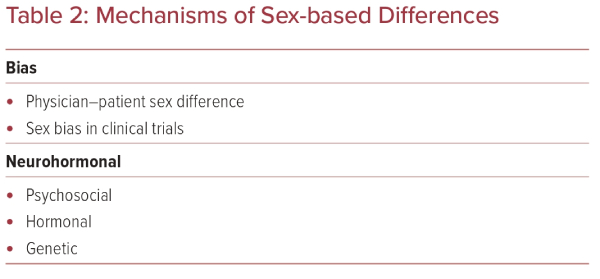

Delayed presentation and delayed care have been studied as causes of worse outcomes in women presenting with chest pain (Table 2). This is evident in the acute setting, with fewer women receiving higher urgency triage in the emergency department, although pre-hospital delay in presentation is also a contributing factor.55,62

Physician–patient sex concordance results in better patient-reported quality of life.61 Female patients post-MI treated by male physicians were found to have an increased mortality risk in a retrospective study of Florida hospital admissions over two decades; this risk was mitigated by male physicians practicing alongside female colleagues or exposure to a female population, but other studies showed no influence.63,64

Bias in Studies

Inclusion of women in CVD studies of the last decade is improving for younger women (aged <55 years) and certain disease populations, but is still lacking.65 This extends to trials evaluating cardiovascular drugs.66 This limitation in existing studies severely limits the generalizability of the data and restricts its clinical applicability.

Neurohormonal Mechanisms

Pain perception differs by sex, and studies suggest a higher sensitivity to somatic pain as well as a higher prevalence of psychosomatic pain perception in women, either independently or comorbid with psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety. This may contribute to the lower prevalence of heart disease in women presenting with chest pain, but the awareness of this difference can contribute to underdiagnosis and undertreatment of CVD in women with this symptom.

Sex and gender differences in pain perception and etiology have been attributed to a variety of causes, including psychosocial, genetic, neurohormonal, and experiential.67

Psychiatric conditions known to be CVD risk factors, such as depression and anxiety, are more prevalent in women, especially at a younger age, and are disproportionately over-represented in young women as both causes and outcomes of acute cardiovascular events.68,69 Psychosocial stress can also be causative of cardiovascular events.

There are known sex disparities in response to stress and its impact on adverse cardiovascular outcomes. In a study of the association of inflammatory response to stress with adverse cardiovascular events, increased circulating biomarkers in response to a stressful event (a speech task) in patients with stable coronary heart disease was a predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events in women but not in men.70

Mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia by perfusion imaging is also more prevalent in younger women than men, with the difference attenuating by 50 years of age.71 Mental-stress induced myocardial ischemia is more predictive of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in men than women, perhaps due to less precise imaging in women owing to artifacts from breast tissue.72 The differential response to stress in women could also underlie the higher prevalence of stress-related cardiomyopathy or takotsubo syndrome in older women, although its prevalence is increasing across age groups.73

Hormonal mechanisms affect presentation and outcomes of chest pain indirectly as modulators of pain perception, and directly via known cardiovascular effects. Estrogen is a known vasodilator with well-known direct effects on the cardiac muscle and vasculature, as well as metabolic functions directly associated with cardiovascular risk. It exerts its effects at the cellular level via upregulation of signaling pathways that enhance cardioprotection and reduce ischemia-reperfusion injury, as well as at the systemic metabolism level, where it has a favorable effect on lipid profiles and insulin sensitivity, and is protective against cardiac hypertrophy.74

Estrogen increases sensitivity to somatic pain, and estrogen antagonism can provide analgesia.75,76 This may contribute to the higher prevalence of non-cardiac symptoms in younger female patients with cardiovascular chest pain.

Indirect evidence for the cardioprotective role of estrogen includes accelerated cardiovascular risk during menopause, and higher cardiovascular risk being associated with earlier menopause.77 Men with estrogen receptor mutations also have a higher CVD risk and earlier onset of disease.78,79 However, menopausal hormone therapies were shown several decades ago in clinical trials to be of no benefit in reducing atherosclerotic coronary disease, while increasing thromboembolic adverse events.80 Newer studies show a safer profile with early use after menopause with lower cardiovascular risk, but menopausal hormone therapy is not recommended for primary prevention.81

Genetic Studies

Genetic effects may in part underlie the response to stress and pain perception, as well as encode direct cardiovascular risk factors.76,82 Genetic effects can manifest as polymorphisms of genes that increase risk preferentially in women (e.g. apolipoprotein E [APOE]), mutations on the X chromosome, or epigenetic alterations due to environmental or hormonal factors.82 However, the X chromosome is commonly excluded from genome-wide association study analyses due to variability in X-inactivation and the difference in number between men and women.82,83

Genes on the Y chromosome are involved in several pathways relevant to chest pain and cardiovascular outcomes. Polymorphisms on the Y chromosome are associated with hypertension, which is more prevalent in men and is a significant risk factor for ischemic heart disease, as well as innate immune activation, increasing risk of inflammation-induced atherosclerosis in men compared to women.84,85

Conclusion

Despite having more cardiovascular risk factors on average compared to men, women are underdiagnosed when presenting with chest pain, largely due to misclassification, misinformation, and underrepresentation in clinical trials.

The novelty of this review is in its extensive comparison of observed clinical differences in men versus women alongside contemporary theories behind these discrepancies, from subjective societal biases and misinformation to objective genetic and hormonal mechanisms under exploration.

Women experience worse outcomes and more mental health strain than men. Genetic and hormonal differences between men and women alone do not sufficiently explain the discrepancies in chest pain evaluation by sex and gender, and healthcare provider bias may play a large role in this disparity. Therefore, it is imperative that the medical community redefine the presentation of chest pain to reflect an accurate clinical picture inclusive of women, addressing their unique and predominant risk factors and their patterns of clinical presentation.