Since the first report of a methodology to assess the appropriateness of medical technologies, the number and application of appropriate use criteria (AUC) has expanded.1 Interest in AUC occurred because of a desire to control the rising costs of medical care, especially in the area of cardiac imaging. For example, ambulatory visits in which a cardiac stress test with imaging was ordered or performed in adults without known coronary artery disease increased from 59 % in 1993–5 to 87 % in 2008–10.2 About 35 % of these tests were in low-risk patients, many without a complaint of angina or even chest pain, thus possibly resulting in unnecessary testing at an estimated annual cost of $501 million. Many believe that the sole use of AUC is to curb treatment overuse, but several of the initial publications using this methodology addressed the underuse of coronary angiography and coronary revascularization.3,4 In addition to the American College of Cardiology, other organizations have developed AUC related to cardiac imaging and to a wide range of topics, from orthopedic procedures to the use of urinary catheters.5–7

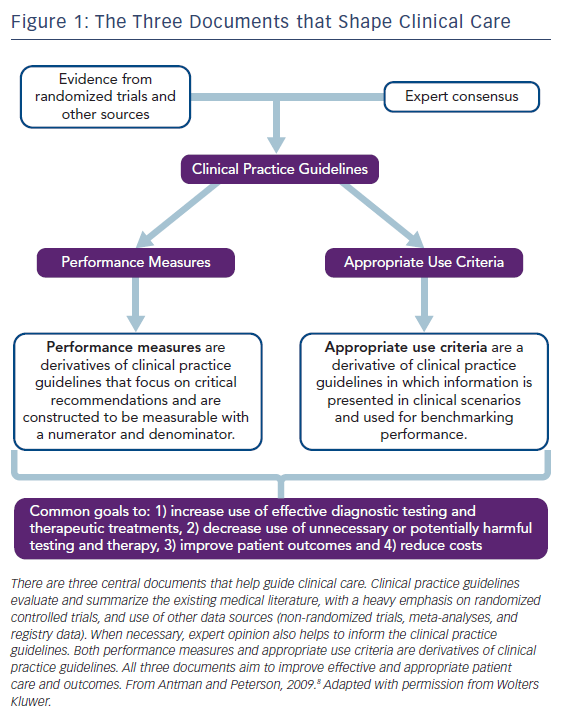

The goal of AUC is to advise clinicians, patients, and policy makers about the reasonable use of testing procedures or therapies to improve symptoms, quality of life, and health outcomes. As such, the AUC comprise one of the three main components used to translate evidence from randomized clinical trials and registries into the delivery of high-value clinical care, see Figure 1.8 The unique format of the AUC incorporates symptoms, risk factors, clinical history, and diagnostic data into brief clinical scenarios (also called indications) to identify patients for whom a test or therapy is appropriate based on the best available evidence or expert consensus.

Effect of AUC on Clinical Care

As AUC have developed, several studies have assessed the effect of AUC on the use of testing modalities and clinical care. For example, Doukky et al. evaluated the use of single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)–myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) in a prospective cohort study of 1,511 consecutive patients undergoing outpatient testing.9 Subjects were stratified according to test appropriateness using the 2009 AUC for SPECT–MPI and were followed for 27±10 months. Among subjects whose MPIs were classified as appropriate or uncertain, an abnormal scan predicted an increase in the occurrence of adverse cardiac events; whereas among those with MPIs classified as inappropriate, an abnormal study failed to predict such events. Moreover, the authors concluded that appropriate MPIs provided incremental prognostic value beyond myocardial perfusion and ejection fraction data. Other studies have shown a reduction in MPI usage related to the AUC, with a favorable financial impact.10 The effect of AUC on the use of echocardiography has also been studied, with variable findings. Some studies show a high rate of appropriate test ordering; whereas others show appropriate testing rates of about 50 % with little improvement over time.11,12

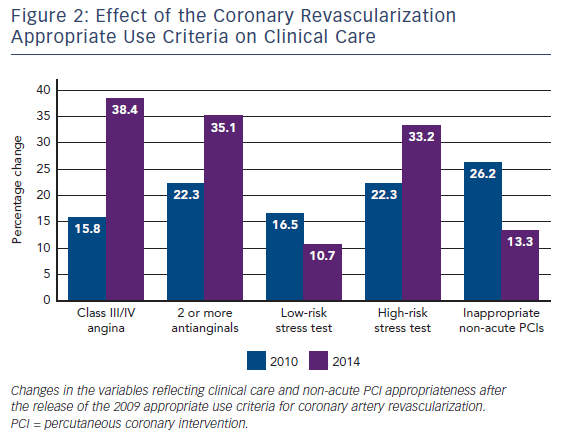

Coronary artery revascularization by coronary artery bypass surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has been the topic of several AUC documents and updates, most recently in 2017.13–15 Desai and colleagues examined nearly 2.7 million PCI procedures from 766 hospitals entered into the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) and showed the effect of AUC on coronary revascularization in clinical care.16 They evaluated trends in PCI utilization and procedural appropriateness, as determined by the first AUC for coronary revascularization published in 2009.13 Among the study cohort, the number of PCIs for acute indications remained similar over the 5 years of observation, whereas the number of PCIs for non-acute indications decreased. Importantly, the number of non-acute PCIs classified as inappropriate decreased from 26.2 % to 13.3 % during the study period, see Figure 2. Over the same period of observation, patients undergoing non-acute PCI had increases in angina severity, the use of antianginal medications and high-risk noninvasive findings. This suggested the AUC caused a favorable change in the use of PCI to focus on patients with important symptoms and stress test abnormalities who were well treated with medications. Similar trends were shown using data from the New York State database.17 In that study, the percentage of inappropriate PCIs for all patients decreased from 18.2 % in 2010 to 10.6 % in 2014, and was even more marked among Medicaid patients (15.3 % to 6.8 %). These changes occurred after the New York Department of Health shared appropriateness ratings with hospitals and announced the intention to withhold reimbursement for stable Medicaid patients undergoing inappropriate PCIs. Delays in obtaining and cleaning data, declining PCI rates over time, and the objections of professional societies all resulted in the denial process not being implemented.18 Likewise, in Washington State, the use of PCI for elective indications decreased over time with simultaneous improvements in PCI appropriateness.19 However, improvements in PCI appropriateness were limited to a minority of hospitals, with the largest decline in PCIs classified as inappropriate. Finally, one of the intended uses of the AUC is to help study variations in care. This was demonstrated in a study examining the relationship between high PCI utilization in certain geographic areas and the number of PCIs classified as inappropriate.20 Data from the Medicare limited data set and the NCDR were used and showed that geographic regions with lower PCI rates had a higher proportion of PCIs performed for appropriate indications. A similar decrease in the utilization of diagnostic angiography alone was shown related to use of the AUC.21

Changes in AUC Over Time

New Terminology

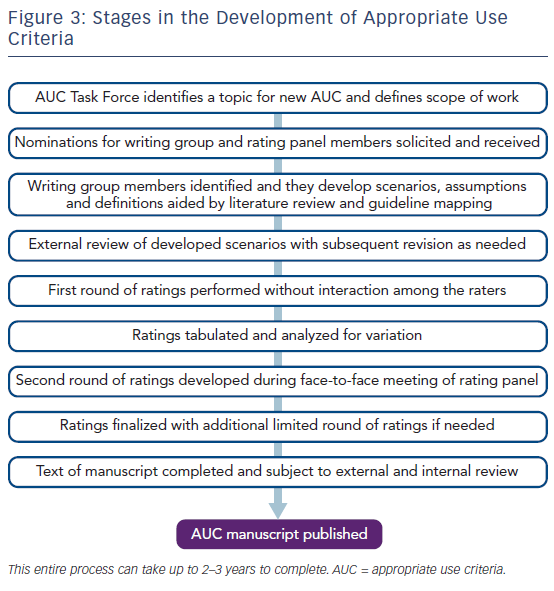

The American College of Cardiology’s efforts to develop AUC has evolved, with the publication of new AUC documents on different topics and updates to the original documents. Although some minor modifications have been made over time, the fundamental methods adhere to the established and validated RAND/UCLA appropriateness method, see Figure 3.1,22 One of the most notable changes has been in the nomenclature used for appropriateness categorization.23 The original classification term for an “appropriate” diagnostic or therapeutic procedure remains and is defined as: “one in which the expected clinical benefit exceeds the risks of the procedure by a sufficiently wide margin such that the procedure is generally considered acceptable or reasonable care.”23 It is important to emphasize that use of the term “appropriate” should not be interpreted as a mandate that all tests or therapies with this rating be performed in all clinical scenarios. Rather, services rated as “appropriate” should be considered reasonable, but not automatically required. Clinical judgment and patient preference are factors that should also be considered.

The prior term “uncertain” has been replaced by “may be appropriate,” now defined as: “At times an appropriate option for management of patients in this population due to variable evidence or agreement regarding the benefits/risks ratio, potential benefit based on practice experience in the absence of evidence, and/or variability in the population; effectiveness for individual care must be determined by a patient’s physician in consultation with the patient based on additional clinical variables and judgment along with patient preferences (i.e., procedure may be acceptable and may be reasonable for the indication).”23 Confusion about the previous term “uncertain” resulted in some stakeholders incorrectly considering this rating as either appropriate or inappropriate, depending on their viewpoint. A rating of “may be appropriate” can be assigned to a therapy or procedure because high-quality evidence about its use in specific patients is deficient. Therapies or services in this category should be utilized based on clinical judgment, patient and provider preferences and include shared decision-making. As emphasized in all of the newer AUC documents, individual coverage determinations should not be made based on a service being rated as “may be appropriate.”

Finally, the prior term “inappropriate” has been replaced by “rarely appropriate,” now defined as: “Rarely an appropriate option for management of patients in this population due to the lack of a clear benefit/risk advantage; rarely an effective option for individual care plans; exceptions should have documentation of the clinical reasons for proceeding with this care option (i.e., procedure is not generally acceptable and is not generally reasonable for the indication).”23 The term “rarely appropriate” was substituted in the revised AUC methodology because of substantial misunderstanding about the term “inappropriate” in earlier documents. Physicians were concerned about the implications of their care being labeled as inappropriate when in uncommon situations it may be the best option for a particular patient. Scenarios constructed for the AUC typically contain three to five clinical characteristics and test results to categorize a group of patients commonly encountered in clinical practice. Unfortunately, this may exclude some subtle and unique findings that might affect decision making for an individual patient. “Rarely appropriate” is not equivalent to “inappropriate,” and thus in some clinical scenarios indicates that a therapy or procedure could still be used. The newer term of “rarely appropriate” better reflects the complexity of patient care and decision making, although physicians should be aware that procedures in this category should be justified by unique patient circumstances, and that these circumstances should be adequately documented to justify the use of rarely appropriate services.

Single Modality to Multimodality Documents

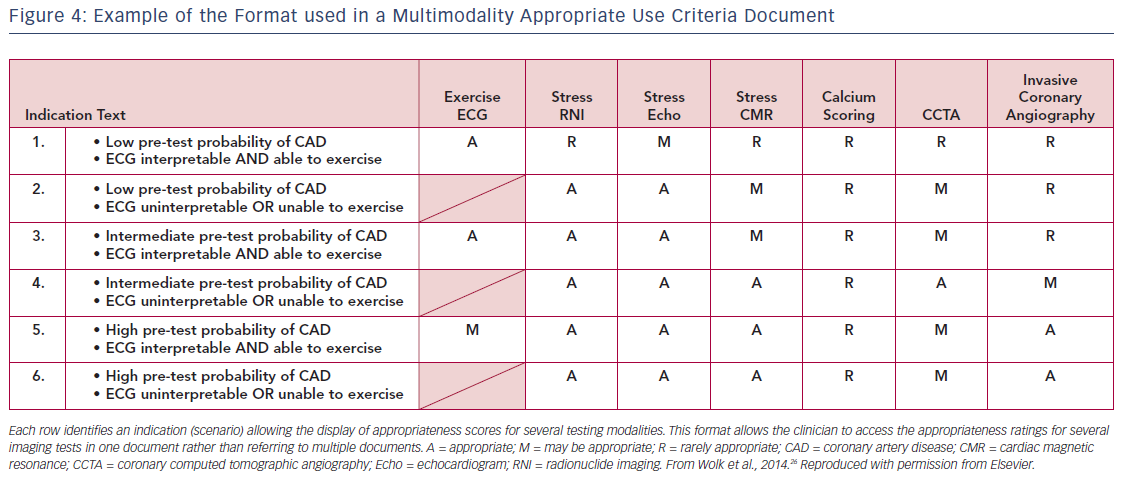

Many of the initial AUC documents focused on the use of a single imaging modality, such as SPECT MPI or echocardiography in clinical scenarios.24,25 In the current environment, there are multiple techniques available for cardiac imaging, each having different characteristics, advantages and disadvantages in certain clinical situations. The AUC Task Force felt it would be easier for the clinician to use one document that provided a side-by-side rating of multiple imaging modalities rather than refer to multiple documents for individual imaging techniques. Using a side-by-side rating format also eliminated concerns about differences in the characteristics of clinical scenarios resulting from the use of individual documents for each test. It is important to emphasize that in this multimodality format, ratings are not intended to be competitive, thereby ranking one test the best among the others. Rather, the intent was to identify and rate all of the imaging tests that would or would not be reasonable for a given clinical scenario and allow the clinician to determine which would be the best for a particular patient in the setting described. Figure 4 shows an example of the multimodality format from the 2013 multimodality appropriate use criteria for the detection and risk assessment of stable ischemic heart disease document.26

The AUC Mandate

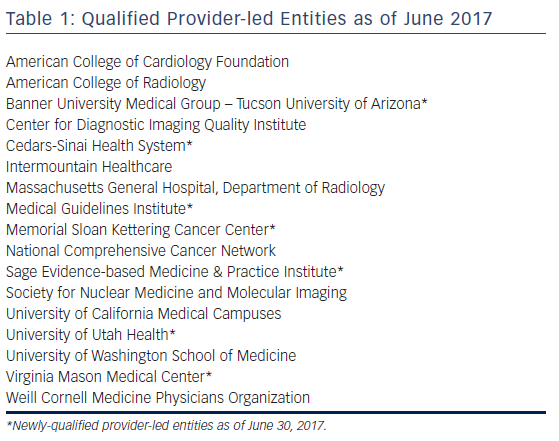

The Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014 contained directives for the use of AUC which were then were amended into the Social Security Act directing the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to establish a program to promote the use of AUC for advanced diagnostic imaging services.27 This incorporated eight priority clinical areas, which in addition to suspected or diagnosed coronary artery disease included suspected pulmonary embolism, traumatic or non-traumatic headache, hip pain, low back pain, shoulder pain (to include suspected rotator cuff injury), cancer of the lung (primary or metastatic, suspected or diagnosed), and cervical or neck pain. In July 2017, the CMS released the proposed 2018 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, which included a proposal to delay the implementation of the AUC requirement until January 1, 2019, but this has now been further delayed until 2020. Currently, advanced imaging services include MRI, CT, nuclear imaging and PET, but not echocardiography. The CMS define AUC as criteria that are evidence based (to the extent feasible) and assist professionals who order and furnish applicable imaging services to make the most appropriate treatment decisions for a specific clinical condition. The directive mandates that, to have claims processed, providers must submit proof that an AUC was consulted through a clinical decision support mechanism. Only AUC developed by entities meeting “provider-led entity” (PLE) standards can be used. Generally, PLEs are national professional medical specialty societies or other organizations that are composed primarily of providers or practitioners who, either within or outside the organization, predominantly provide direct patient care. PLEs must apply and then reapply every 5 years to the CMS and to be qualified must adhere to evidence-based processes and other requirements when developing or modifying the AUC. A list of the current qualified PLEs is given in Table 1. The second part of the AUC mandate requires the use of a Clinical Decision Support Mechanism (CDSM). CDSMs are the electronic portals through which a clinician accesses AUC during the patient encounter and by which specific patient information and testing results from the electronic health record are incorporated to determine the appropriateness rating. With a fully-embedded CDSM platform, practitioners interact directly with their primary user interface, minimizing interruption to the clinical workflow. For each interaction, the CDSM must record a unique Decision Support Number that connects the provider’s National Provider Identifier number, the selected indication and service, and the applicability of AUC to that order. Without this information associated with the bill to Medicare, payment is not made. Similar to qualified PLEs, CDSMs must be qualified as meeting the requirements of the CMS. Those meeting the requirements are posted on the CMS website.28 The value of using a point-of-care CDSM was demonstrated in a prospective trial that showed a reduction in the inappropriate use of all cardiac imaging modalities from 22 % to 6 %.29

The AUC Summit

In part stimulated by the AUC mandate, and because of the increasing number of organizations becoming qualified as PLEs, a 1-day cardiovascular AUC summit meeting was organized by the American College of Cardiology and held in Washington, DC, on August 9, 2017. The meeting was led by an independent moderator and attended by representatives from the CMS, key leaders from the qualified PLEs, stakeholders from several primary care professional organizations and leaders from companies developing CDSMs. The goals of the summit were to develop recommendations for: forming effective partnerships and collaborations among those who will develop AUC; and implementation strategies, communication to clinicians, and tools for clinicians to utilize to meet the AUC mandate. Workgroups consisting of attendees are being formed to address key areas in preparation for the AUC mandate. One of these areas will focus on the importance of achieving some level of harmonization among the appropriateness ratings from the different PLEs. Data comparing AUC from different professional organizations are limited, but a study comparing the ratings of two professional organizations for myocardial perfusion imaging found substantial discordance.30 When comparing ratings within a cohort of 592 patients, 18.8 % could not be matched to a rating from the other organization, 59.0 % had the same appropriateness rating, and 22.3 % were discordant. Overall, the agreement of appropriateness between the two methods was poor. Discordant AUC recommendations will lead to confusion for all stakeholders in this process. Hopefully, by working together a structure can be developed that will preserve the ability of independent qualified PLEs to develop AUC yet result in harmonization of the recommendations.

Conclusions

As the entire healthcare system moves away from a fee-for-service structure to one based on the quality and value of services, the use of AUC will likely expand. As this occurs, it is important to emphasize that the AUC were never intended to be an arbitrator of payment for an individual patient. Rather the AUC were developed as a method to characterize, study and refine care and the use of medical resources among patient populations. Used for this intent, the AUC have potential to be one of several tools available to help reform the delivery of healthcare in the future.