Seminal clinical trials conducted in the balloon angioplasty and bare metal stent era established the superiority of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) as compared with aspirin monotherapy or anticoagulation with respect to the prevention of thrombotic events.1,2 Other studies found that the benefits of DAPT are durable for at least 1 year and extend to patients with acute coronary syndromes.3–5 However, iterative advances in stent design lowered the thrombotic potential of these devices, thereby altering the risk–benefit calculus for prolonged durations of DAPT.6,7 Moreover, numerous studies have shown that bleeding confers a strong and independent risk for mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), thus rendering the prevention of bleeding an important clinical priority.8–10

While several studies have shown that short DAPT durations followed by aspirin monotherapy may be safe and feasible in relatively low-risk patients, extension to higher-risk patient and lesion subsets remains less certain.11,12 An alternative approach that might preserve the benefits of strong P2Y12 inhibition while lowering bleeding involves the cessation of aspirin and continuation of a potent P2Y12 inhibitor after an initial course of DAPT.

Rationale of the Trial

The What is the Optimal antiplatElet and anticoagulant therapy in patients with oral anticoagulation and coronary StenTing (WOEST) trial was the first study to examine the effect of an aspirin-free strategy in the context of PCI by comparing warfarin, clopidogrel, and aspirin with warfarin and clopidogrel over a period of 1 year among patients with AF.13 In this study, the withdrawal of aspirin led to a significant reduction in bleeding with no change in thrombotic events.13

Other studies using alternative direct oral anticoagulants recapitulated these observations, and an initial aspirin-free approach is considered optimal in most patients receiving oral anticoagulation and clopidogrel after PCI.13–16

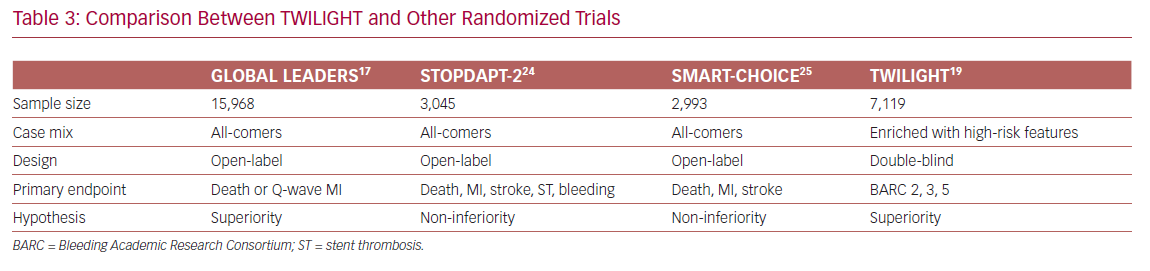

In contrast, the GLOBAL LEADERS trial was the first examination of an aspirin-free strategy in a large, all-comer PCI population not receiving an oral anticoagulant.17 In this trial, ticagrelor monotherapy for 23 months was compared with conventional DAPT followed by aspirin alone. The experimental approach did not significantly reduce the risk for death or Q-wave MI over a period of 2 years, a null result that has been attributed to the inclusion of relatively low-risk patients, variable levels of drug adherence, or the lack of central adjudication.17

Hence, the benefits, or harms, of ticagrelor monotherapy in patients at higher risk for either ischemic or bleeding complications remain unclear. In addition, it is plausible that higher-risk patients will derive a larger benefit from a therapeutic intervention aimed at lowering bleeding.

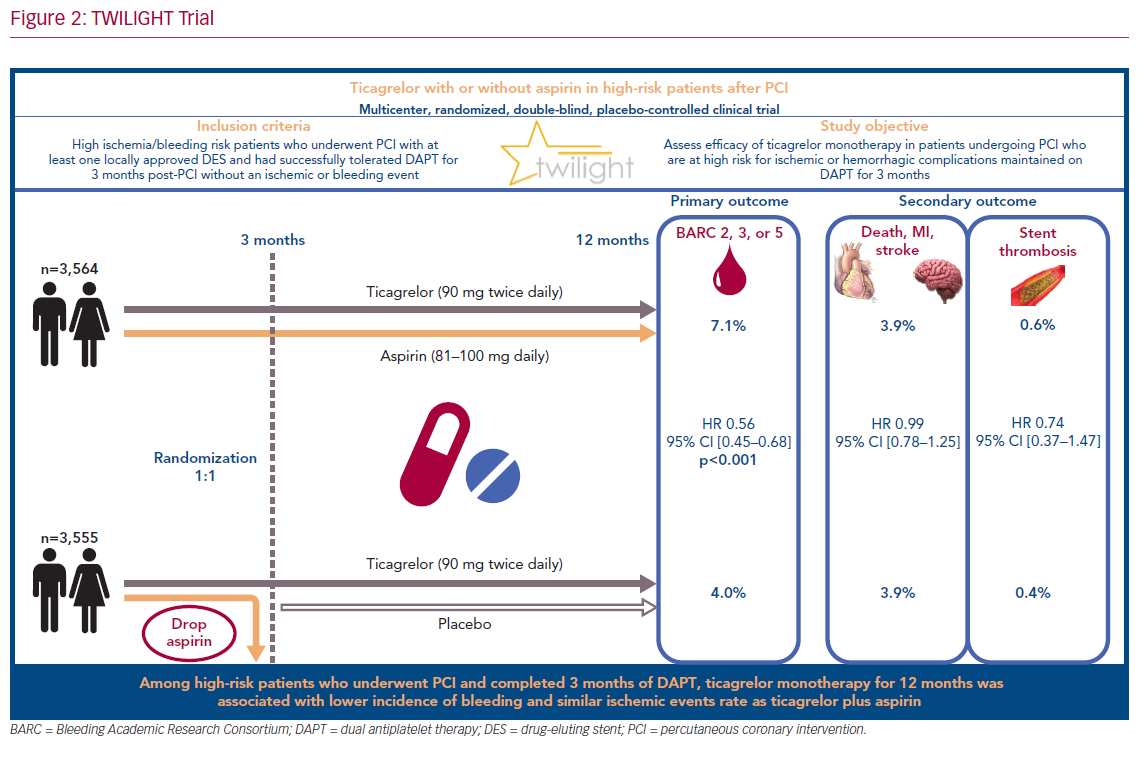

Accordingly, we designed the Ticagrelor With Aspirin or Alone in High-Risk Patients After Coronary Intervention (TWILIGHT) trial to test the hypothesis that ticagrelor monotherapy would yield a significant reduction in clinically relevant bleeding while not increasing ischemic risk, as compared with ticagrelor plus aspirin among high-risk patients undergoing PCI who had already completed a 3-month course of DAPT.

Study Design

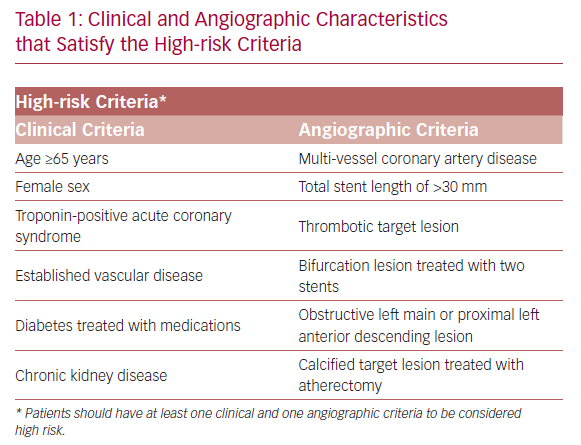

TWILIGHT (NCT02270242) is a randomized and double-blind trial conducted in 187 medical centers across 11 countries.18,19 The patients selected for participation underwent successful implantation of at least one drug-eluting stent, followed by discharge on a regimen of ticagrelor plus aspirin, as intended by the treating physician. Selected patients were high risk, as defined by at least one clinical and one angiographic feature (Table 1). Patients with ST-segment elevation MI, cardiogenic shock, ongoing long-term treatment with oral anticoagulants, or contraindication to antiplatelet therapy were excluded.

All enrolled patients received DAPT, consisting of ticagrelor (90 mg twice daily) and enteric-coated aspirin (81–100 mg daily) for 3 months after index PCI. Patients who showed adherence and did not have a major bleeding or ischemic event (stroke, MI, or coronary revascularization) at 3 months were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to either aspirin or placebo in addition to continuation of open label ticagrelor for an additional 12 months.

A secure web-based system was used to perform the randomization. Sequences were randomly generated by blocks of four, six, and eight patients, and were stratified according to treatment site. Randomized patients were followed up by phone at 1 month and in person at 6 and 12 months after randomization. Adherence to medications was evaluated using manual pill counts.

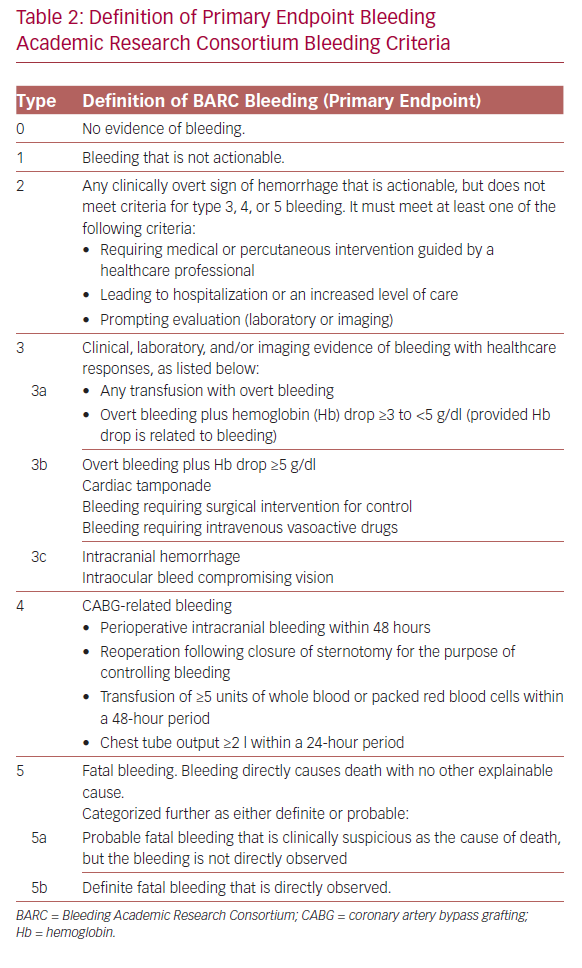

The primary outcome of interest was bleeding events, defined as type ≥2 according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria (Table 2).20 The secondary outcomes were mainly ischemic events, including death from any cause, non-fatal MI or stroke, and thrombosis. Both primary and secondary outcomes were observed between randomization and the 1-year follow-up period using a time-to-event analysis. All clinical events were externally adjudicated by an independent committee whose members were blinded to therapy assignment.

The study was powered to detect a difference in the primary endpoint of BARC type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding, based on a superiority assumption. A sample size of 8,200 patients was required to achieve 80% power in the detection of a 28% lower incidence of bleeding in the experimental group, assuming an incidence of 4.5% at 1 year in the control group (type I error rate of 0.05). Similarly, for the secondary endpoints, 8,200 patients were required to achieve a power of 80% in ruling out an absolute difference in risk of 1.6 percentage points (one-sided type I error rate of 0.025).

The primary endpoint of bleeding was analyzed using an intention-to-treat approach. In contrast, the analysis of ischemic events was completed by only including randomized patients who completed the treatment originally allocated (per-protocol approach).

Results

Out of 9,006 patients selected for participation, 7,119 were randomly assigned in a 1:1 fashion at 3 months to either ticagrelor plus placebo or ticagrelor plus aspirin with an intention-to-treat. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were very similar between the two arms: the mean age was 65 years, women represented 24% of participants, and the prevalence of diabetes and chronic kidney disease was approximately 40% and 17%, respectively. Multivessel coronary artery disease was prevalent in 63.9% of patients in the experimental arm, and 61.6% of those in the control arm.

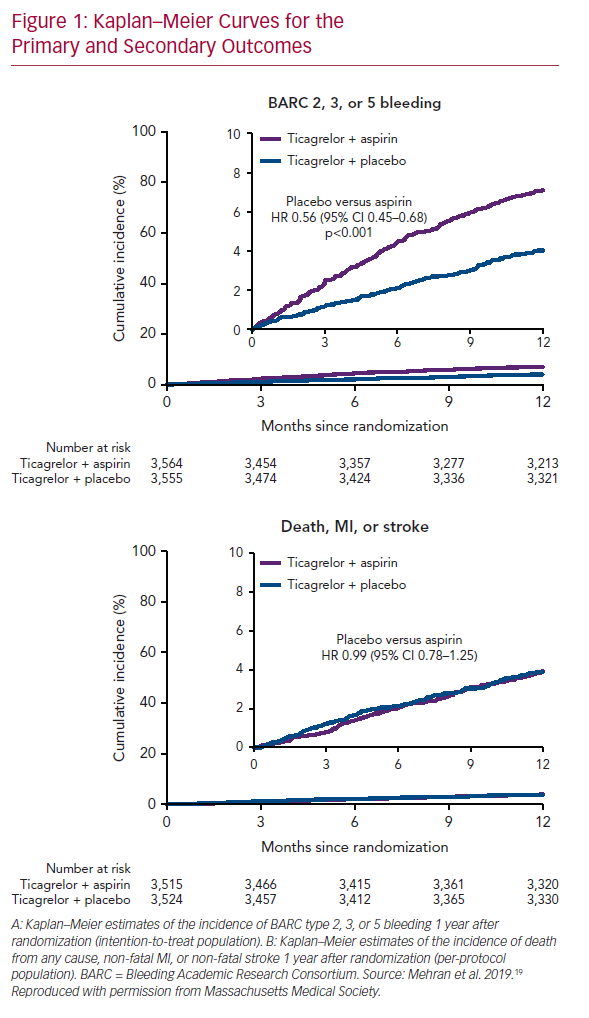

The primary endpoint, bleeding events (BARC type 2, 3, or 5), occurred in 7.1% of patients who received ticagrelor plus aspirin, and 4.0% of those who received ticagrelor plus placebo (HR 0.56; 95% CI [0.45–0.68]; p<0.001; Figure 1A). Secondary endpoints, mainly ischemic events (including all-cause death, non-fatal MI, or non-fatal stroke), occurred similarly in the two arms: 3.9% in those who received ticagrelor plus placebo, and 3.9% in those who received ticagrelor plus aspirin (HR 0.99; 95% CI [0.78–1.25]; Figure 1B). These findings were consistent across all subgroups analyzed (age, sex, race/ethnicity, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, BMI, indication for PCI, total stent length, prior MI, and multivessel disease).

Discussion

Transition to ticagrelor monotherapy after 3 months of DAPT in high-risk patients who received a drug-eluting stent was associated with a significant decrease in the incidence of bleeding events (44% lower risk of BARC type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding). The benefits of aspirin withdrawal at 3 months extended to severe bleeding events (BARC type 3 or 5) and across different bleeding scales (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction [TIMI], Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries [GUSTO], and the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis [ISTH]).21–23

In contrast, ischemic events occurred similarly in both arms, indicating that dual therapy does not confer additional protection from death, MI, and stroke. In other words, ticagrelor monotherapy led to a lower bleeding events rate without compromising the protection from ischemic events, as compared with a dual therapy regimen. These findings were consistent with some previously published studies, but conflicted with others. The differences are mainly due to variations in clinical trial design and execution (Table 3).

Two randomized clinical trials, ShorT and OPtimal Duration of Dual AntiPlatelet Therapy-2 (STOPDAPT-2) and Smart Angioplasty Research Team: Comparison Between P2Y12 Antagonist Monotherapy vs Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients Undergoing Implantation of Coronary Drug-Eluting Stents (SMART-CHOICE), showed a significant bleeding risk reduction without a change in ischemic events when switched to clopidogrel monotherapy after 1–3 months of DAPT.24,25 In contrast, GLOBAL LEADERS showed that 1 month of DAPT followed by 23 months of ticagrelor monotherapy did not reduce the risk of bleeding as compared to dual therapy.17

The contradictory results between TWILIGHT and GLOBAL LEADERS can be explained by differences in study design: the first is double-blind, a high-risk population who received monotherapy for 12 months; whereas the second trial is open-label, an all-comers population who received therapy for 23 months. In addition, the control arm in GLOBAL LEADERS was maintained on aspirin, whereas in TWILIGHT it was maintained on ticagrelor plus aspirin. Finally, bleeding events were self-reported in GLOBAL LEADERS, whereas adjudication committees evaluated events in TWILIGHT.

All these differences could explain the attenuated beneficial effect of aspirin withdrawal in GLOBAL LEADERS as compared with TWILIGHT. Indeed, in patients maintained on ticagrelor monotherapy, the relative incidence of BARC type 3 or 5 bleeding was 14% lower in GLOBAL LEADERS compared with 51% in TWILIGHT.17

The main strength of the TWILIGHT trial is mainly in including high-risk patients who are highly prone to primary or secondary endpoints at 12 months follow-up. Consequently, shortening exposure to dual antiplatelet agents in this vulnerable population has a great impact on bleeding reduction without compromising the ischemic protection. Nevertheless, the TWILIGHT results are only applicable to patients satisfying pre-specified clinical and angiographic features (Table 1), and cannot be generalized to patients with ST-segment elevation MI or non-acute coronary syndrome on presentation.

Moreover, 36% of all patients included in the study were either asymptomatic or had stable angina. A dual antiplatelet regimen consisting of aspirin and clopidogrel is usually recommended by all guidelines for such patients.11,26 Hence, it is expected that the use of ticagrelor rather than clopidogrel in non-acute coronary syndrome patients results in a higher incidence of bleeding events without a significant change in ischemic events.

Consequently, one might assume that the beneficial effect of ticagrelor monotherapy should not be extended to all PCI patients, and especially to those with stable disease. However, all patients enrolled in TWILIGHT, including those with stable disease, had at least one clinical and one angiographic characteristic that placed them at high risk for complications following PCI, and hence they were prescribed a more potent P2Y12 inhibitor (ticagrelor rather than clopidogrel).

The present study had several limitations. First, the lack of power to detect differences in the risk of stent thrombosis and stroke (considered as rare events). Second, only high-risk patients were included; hence, the results may not be applicable to low-to-intermediate-risk patients. Furthermore, the results are also not applicable to patients who satisfied the high-risk criteria but did not tolerate DAPT in the first 3 months. Third, more ischemic cerebrovascular events were recorded in patients receiving ticagrelor monotherapy; however, because of the low number of events (24), no conclusion can be made. Fourth, the primary endpoint included bleeding events of different severity, which might affect the risk–benefit calculation for ticagrelor monotherapy. Fifth, a lower than expected incidence of the composite endpoint for the secondary outcomes may have biased the study results toward the null. Sixth, patients with ST-segment elevation MI on presentation were excluded, which could affect the generalizability of the results to this high-risk population.

Conclusion

Transition from dual antiplatelet therapy consisting of ticagrelor plus aspirin to ticagrelor-based monotherapy in high-risk patients at 3 months after PCI resulted in a lower bleeding events rate without an increase in death, MI, or stroke (Figure 2). The ongoing challenge will be in integrating the findings of TWILIGHT with the abundant evidence from previous studies supporting long-term DAPT in patients with low bleeding but high ischemic risk. Nonetheless, the decision to switch from DAPT to ticagrelor monotherapy remains at the discretion of each physician’s clinical judgment and the patient’s specific baseline characteristics.